Impact Magazine

Vol 42, No.3

March 2008-03-27

pp.4-7

A profound cleavage presently obtains in the Philippine State that divides Church and Government on mining issues.

Government – from the Congress that gave us the Mining Act to the Executive Branch that so eagerly implements it and the Judiciary that as brazenly upholds it – forms one side of the divide.

The other side is the Church. Define her in any way you want: as institution, as people in civil society and ecclesial communities, as Magisterium, that is, Pope and Bishops together, or Bishops alone in each diocese and as a group, - or as a mixed commission of Bishops with their authority and Religious Orders with their charisms united in serving God’s people. When it comes to the issue of mining, this Church is, today, one and quite tenacious.

Government says that what they do, what they propose, what they advocate in the area of mining – are all legal. At one time the Supreme Court declared otherwise, viz. that the whole thing was not legal and not constitutional. However, it changed its mind in record time: now everything is legal, and constitutional. After all, the Supreme Court is supreme and, right or wrong, the law is whatever that Court says it is.

Unfazed, the Church, on the other side, talks of morality, of ethics, of what is right and wrong - not only describing what is, but prescribing what ought to be. And it has come to this – that, in the area of mining, what the Government calls legal, the Church denounces as immoral.

We have here a situation reminiscent of the early Christian era during the late Roman Empire when both Western and Eastern Church leaders denounced Roman law, no less, as immoral in its idea and practice of the absolute ownership of Earth by a few for the benefit of a few at the cost of nature’s destruction, in violation of the integrity of creation and the intention of the Creator.

From the Church’s viewpoint, what is legal is a matter of factual contingency. It is another thing to determine whether the human legal arrangement is just. If it were to be unjust, said Saint Augustine in the fifth century of the Common Era, “What would the great empires be but teeming broods of robbers?” By “human law therefore – by the law of the Emperors” you can do many things that you ought not to do. Hence, past a certain threshold, when the legal is patently immoral, all effective efforts must be made to change the law – a situation most Philippine bishops now see in the area of mining.

As exemplified by the interventions of Bishops Bastes and Jose Rojas in the Rapu-Rapu Commission, the Philippine Bishops hold that in the course of economic development and growth, many human acts can be either right or wrong relative to their effects on the house of life we call the environment. They refer to environmental ethics or “geo-ethics”. Human acts are rarely value-free or ethically neutral. They are always either right or wrong. And when they are wrong – no matter what great profits they had brought to some corporations, or revenues to some governments, and prosperity to some individuals and social sectors – if and when those human activities we refer to were essentially wrong, they ultimately and inevitably would have to bring worse problems and deeper crises, for truth is one: the truth of science, the truth of economics and the truth of ecology are one many-sided, non-conflictual truth.

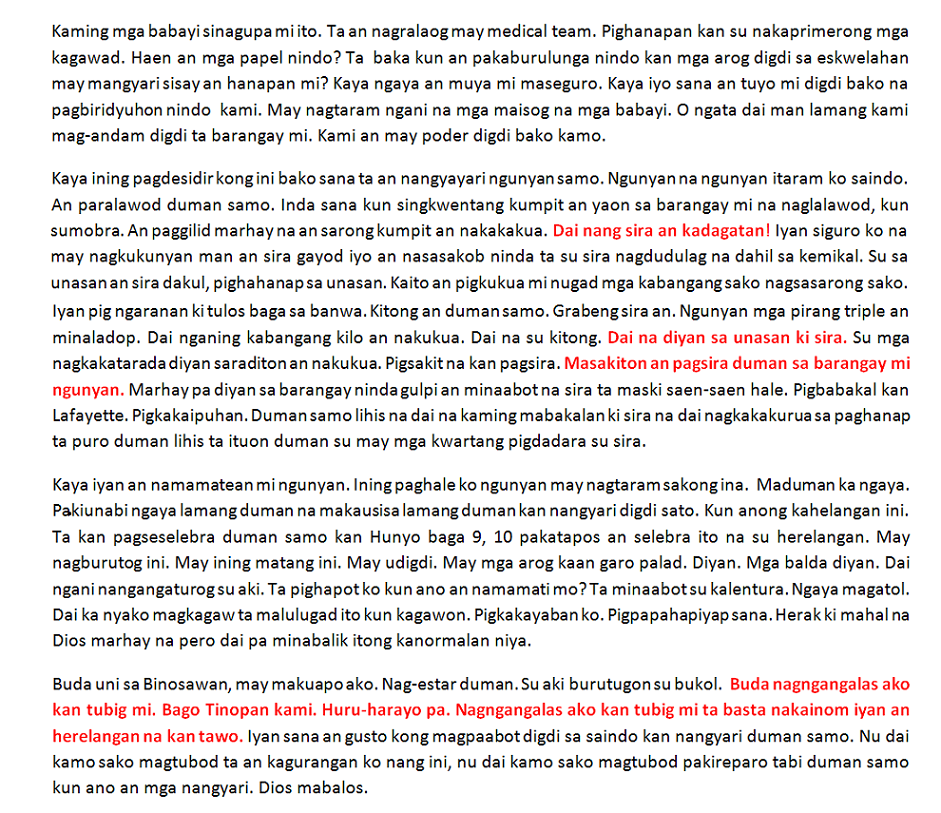

For instance, a certain way of exploiting some mineral resources could bring irreparable, and therefore irreversible, damage to the environment. Any damage to the environment in this way can in turn bring irreparable harm and injury to human health. The Minamata disease in Japan comes to mind, which took years and years to establish, before effects could be linked to original causes beyond reasonable doubt – just like what happened in the Philippines at Marinduque and Rapu-Rapu.

Another fact is the non-renewability and non-inexhaustibility of mineral resources. Once they are depleted, there is no way that they can be replaced or restored. It is good to remember that the essential resources upon which progress depends are not inherently and exclusively created by human technology. They are inherently natural in origin and are fundamentally in limited supply.

The biology of natural systems simply does not exist within and is not subject to human artifice. It is we who exist within and are subject to the natural setting. We do not exist apart from but as a part of the natural world.

A given mining operation, therefore, will have to be viewed by people and Government according to this perspective and first be evaluated as either ethically right or wrong, good or bad, before it could even be considered legal or illegal, or before it can be judged economically profitable or non profitable. Without a full respect for the principles of geo-ethics, the exploitation of mineral resources can be very dangerous indeed.

Foreign spokesmen given exaggerated hospitality in this country have been observed to keep repeating like a mantra, Hitler-like, the line that the Mining Act which the Philippine Church seeks to review is “the best mining law in the world”, while immediately hiding with malicious glee the enthymeme that yes, it is the best in the world for their interests, from their point of view.

The Bastes Commission Report remarked that people of earth have a duty to govern the world with justice and harmony even as they use for themselves the resources of nature’s bounty. Church leaders are not – they could not be against mining per se. Mining has been an important part in the historical development of civilizations – from first (agricultural) to second (industrial) to third (information) wave of social formations.

Industries need minerals to support the production and flow of basic goods and services. The production and availability of a broad range of metals are essential to modern life. Throughout human history, economic progress has been dependent to a large extent on the availability and use of metals.

The Church would lay accent on the fact that metals can be reused and recycled indefinitely without loss of their properties.

The Philippines is a part of earth that is so incredibly rich in gold, silver, copper, nickel, chrome and zinc that the valuation of the mineral wealth within our territorial limits is more than a trillion dollars’ worth, at least.

However, the Philippine Government and the Filipino people do not seem to actively subscribe to the fundamental geo-ethical principle of stewardship. In fact, they do not really manage and control mining as a crucial part of basic industry.

Stewardship, in general, means the protection, care and proper use of this world’s resources. According to this principle, human beings are called by nature to nurture, protect, use, order, and adorn the earth and all living and nonliving creatures in harmony with and obedience to the fundamental laws written into the very nature of all things. Thus, the steward is more a manager, and not an absolute owner.

We are called to care for the special environment and biodiversity our country has been gifted with, including all her natural wealth and mineral resources – in short, to be responsible as stewards for the national patrimony towards the attainment of the common good.

For, no matter how huge our mineral deposits, they are finite. It would really make for good stewardship to develop our own basic and medium industries and make sure we have enough for building a strong industrial economy. We can’t just give up on the possibility of seriously developing in our country an integrated mining industry. There is room for foreign investments – room. It is crazy to give foreigners the whole house. That would be tantamount, again, to giving up on our stewardship obligation and vocation.

Today, the Mining Act is quite deceiving. It does not include the crucial provision of the government's pre-tax share of the cash flow generated by a mining project. In most countries around the world where there is mining this pre-tax share representing the national patrimony averages a hefty 38% (Chile 15.00% ,Bolivia 27.06% ,Venezuela 32.82% ,Peru 36.52%, United States 36.61%, Mexico 37.21%, Botswana 40.10%, Brazil 40.85%, Argentina 46.13%, Canada 46.71%, Guyana 48.16%, Australia 50.60% ) ! In the Philippines , the share representing the national patrimony is exactly zero percent.

The government's “share” in the mining deals only includes taxes, duties, and other fees paid by the contractors. And the payment of these fees does not immediately benefit the Philippines as the contractors are given the privilege of first fully recovering their pre-operating and property expenses before paying their financial obligations to the government, not to mention the aggressive grant of tax holidays to foreign investors in mining, which does not make sense at all since mining is that kind of investment which is neither market-seeking nor efficiency-seeking so much as clear asset-seeking.

In mining, the Philippines is such a give-away country – one wonders why any one should even respect it as sovereign at all. The Mining Act expressly states that the excise tax on mineral products shall constitute the "total government share in a mineral production-sharing agreement," which under the Tax Code is only two percent of the market value of the gross output of the minerals. In effect, the government concedes to the foreign corporation practically for free its beneficial ownership over the mineral resources. Curiouser and curiouser… is Government’s effort in all three branches to convince us that tax is the same as ownership share!

What we should always make clear is that, under the principle of stewardship, mining projects that cannot absorb the environmental and social costs of modern mining should not be allowed to proceed. Then we won’t have the case of a Lafayette , such as we have seen for many years now.

Stewardship, true enough, is not only about the preservation and conservation of nature. It includes the creative transformation of nature, represented by human ingenuity and technology. In performing this task, however, human beings must recognize that they can only proceed within a certain limit. The resources with which they must work are not necessarily inexhaustible. Stewards should be co-creators, not exterminators.

Nature is to be creatively transformed, not relentlessly exploited. Our slogan should be, “Need rather than greed.” We should not encourage people to be simply driven by the desire to satisfy wants and wantonly engage in research and experimentation without taking into consideration risks and negative consequences.

We need to underscore the present situation in our country that needs to find new ways of thinking and new ways of planning and controlling mining activities. A considerable improvement of ethical climate is needed and hopefully some of the principles of geo-ethics will go a long way in dispelling muddled thinking and giving new clarity of direction. It is not always easy.

Despite its boast of legality, Government does not always find it easy just to follow the rule of law rather than the culture of privilege and impunity. In the case of Rapu-Rapu, for instance, following the spirit and letter of the law, DENR should just have cancelled the Environment Clearance Certificate (ECC) of a recidivist firm, and if allowed to re-apply, let it undertake the drawing up of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and propose an Environmental Management System ( EMS ), precisely as the law requires, and then let an awakened citizenry watch a reformed DENR do its job.

The Bastes Commission found strong indications to believe that the firm underreported its production of ores and of processed gold and silver to the MGB or Mines and Geosciences Bureau thereby reducing the basis, and ultimately, the value of the excise tax they would have to pay the government.

Bastes warned that Lafayette only wanted to have DENR hostage in their threat that if their mining permit or ECC were cancelled, they’d just walk away and leave DENR with the mine tailings and the pollution and the crisis. And DENR was just too weak to defend the environment and people’s health and welfare. It surrendered, in the name of attracting more investments – of the credit card variety. This is the type that brags, “Have permit and there will be banks to give you a credit line.”

Now the Lafayette mine is more than a financial mess. The poster boy of the Administration’s foreign mining interests has filed for bankruptcy! Worse - it is an environmental and social failure. How many forewarned the Administration and the DENR that the project is not socially, technically, environmentally and financially feasible but, still, they allowed it to proceed. Should they not be held accountable along with Lafayette to rehabilitate the island and compensate the local residents for damages done by the mine?

And has the important lesson been learned? A company that fails to obtain and retain a social licence to operate, in other words one that operates without community approval, is simply not viable.

These are not the best of times. The world demand for our minerals is at a new high. And Government is at a new low – so weak and so unwilling to put people’s welfare and environmental conservation above the fetish of investment promises that become a source of even greater frustration all around. These, however, are the most challenging times. Maybe now bishops and religious people may succeed in the formation of enough numbers of the lay faithful so that the latter can seriously start transforming the world.

Charles Avila has been with peasant organizing since the early 1960s and is presently the National Chairman of the Philippine Association of Small Coconut Farmers’ Organizations. He is President of Great Work Movement (Phil) and was Vice-Chairman of the Rapu-Rapu Fact-Finding Commission.

No comments:

Post a Comment