Introduction

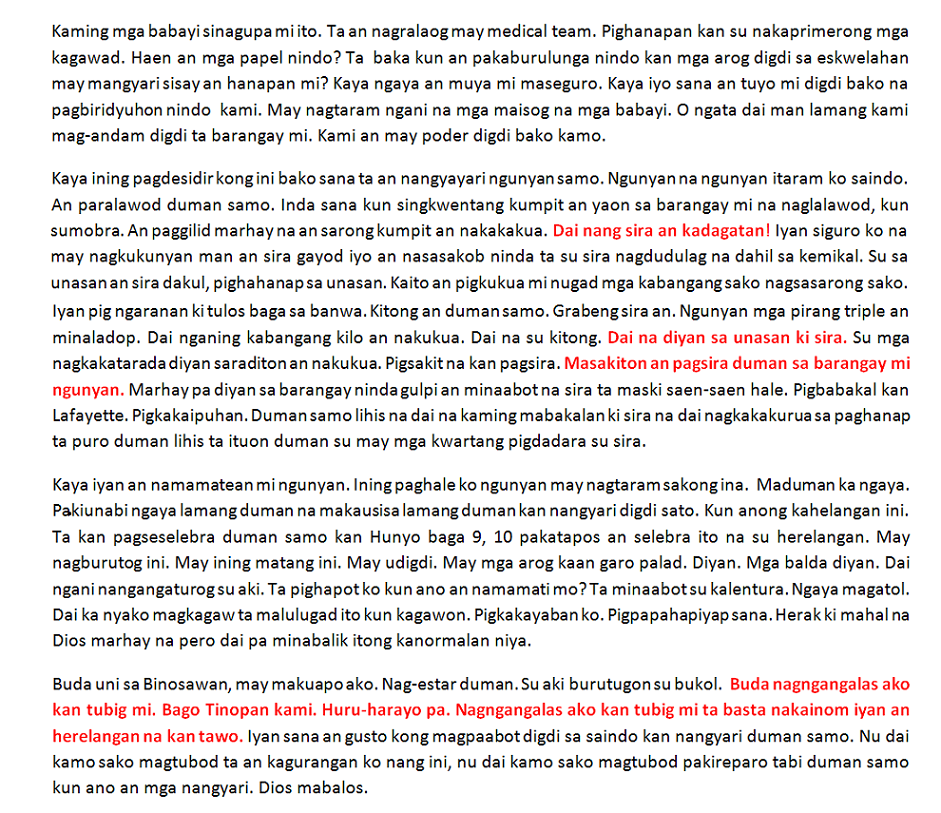

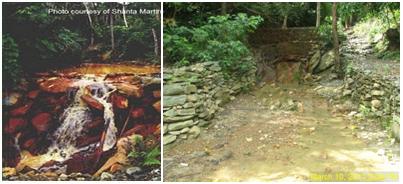

On October 11 and 31, 2005, mine tailings or wastewater from ore processing of Lafayette Philippines, Inc. (LPI), an Australian mining company, spilled to the creeks and into the sea, directly killing fish, shrimps and crustaceans in the immediate and surrounding fishing areas, thus affecting the livelihood of local communities in Rapu-Rapu Island, Albay, Philippines. It was found out that the spillages had high level of cyanide. On November 7, 2005, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) suspended LPI’s operations until investigation and appropriate measures would be implemented.

Anti-mining groups which included the local Catholic Church, non-government organizations (NGOs) and local people’s organizations (POs) revived and reiterated their call to revoke the mining permit of LPI. What they feared had come to reality.

This paper generally tackles and analyzes the conflict between LPI, a mining company, and anti-mining groups on the mining operations being conducted in Rapu-Rapu Island . In particular, this paper focuses on the spillage incidents and how they impacted on the whole conflict. It is hypothesized here that the conflict and spillage incidents are exacerbated by the state’s inefficiency on environmental governance.

The incidents prompted an investigation by an independent group which showed that the discharge of cyanide did not meet the standard set by Anti-Pollution Laws and recommended improvement in the tailings pump and pond and measures to ensure effluent output or wastewater from the mine would meet the standards set by law. As a result, the DENR imposed the maximum 10.7 million pesos in fines and penalties.

The anti-mining groups were not satisfied with and did not trust the findings and recommendations of the investigation. Sharing their sentiments were some Catholic bishops who wanted to stop the mining operations in Rapu-Rapu Island.

To appease the growing confusion and question on what really happened in Rapu-Rapu Island, President Gloria Arroyo issued Administrative Order (AO) 145 which created the Rapu-Rapu a fact-finding commission headed by a Catholic bishop on March 10, 2006. The commission released its comprehensive report on May 19, 2006 with its findings and recommendations. Major of which was to cancel the mining permit of LPI. However, the state did not heed the commission’s recommendation. Instead, on June 11, 2006, the DENR gave LPI a three-stage 30-day test run of its implemented measures and its soundness to operate again. After that, another 60-day test run was granted to LPI for its limited operations.

On February 8, 2007, the DENR allowed full resumption of mining operations of LPI in Rapu-Rapu Island to the dismay of the anti-mining groups.

Applying a Conflict Model of Analysis (C.R. SIPABIO)

To have a better understanding of the conflict in Rapu-Rapu Island, this paper makes use of conflict analysis model known as Context, Relationship, Sources, Issues, Parties, Attitudes/Feelings, Behaviours, Intervention, Outcomes (C.R. SIPABIO) by Amr Abdalla, et. al. (2002).

Contextual Factors (geography, economic, religion)

Endowed with rich mineral deposits in a 5,589-hectare land, Rapu-Rapu Island is located 350 kilometres southeast of Manila . The topography of the island is dominated by rolling hills and mountains with steep slopes and dotted by plains along the shoreline for settlements. These characteristics, being a small island with fragile ecosystem, distant from the city and coverage of media, and of rolling hills and mountains, are the contentions of the anti-mining groups to disallow mining which would disturb ecosystem and pose threats to the marine life of the island.

In economic terms, the island is part of relatively poor 4th-class municipality. Its means of livelihood for the islanders are fishing and farming. Mining operations which put in a lot of money to the island had displaced many farmers from their field and fishers to work in the mine. Regular access to cash income attracted these farmers and fishers to abandon their previous livelihood. A number of farmers and fishers though expressed their apprehension and concern of the potential effects of mining on their land, sea and the environment as a whole from which they source their living. For them, security is tied with the state of environment (Brown 2005).

Religion and identity play some role in the conflict. Majority of the population are Catholics that make them perhaps identify with the struggle and cause of the church. This prompted the local Catholic church to actively participate in the public hearings in behalf of the parishioners. It became a moral obligation of the local Catholic church to act in behalf of the locals when they were faced with dilemma such as this. Besides, the only organized group of people in the island is the Catholics through their church.

Relationship Factors (power, patterns, bond)

With money and resources invested in the island, the mining company wanted to show that it means business. It enticed people and local government units with jobs, infrastructure projects, revenues, and social services previously unimagined. Clearly, LPI was acting behind the power of its money and resources. However, a number of farmers and fishers and the local Catholic church were on the moral high ground, as it were, to oppose the mining operations.

Having identified the two sides of the conflict, it became apparent their patterns of behavior to further their opposing stand. LPI always invoked the mining permit that the government had issued to them. It reminded the anti-mining groups that it underwent rigorous processes and social acceptability required by law before it was granted the permit. It also boasted some of the completed and improved social services delivery, infrastructure and utility projects which the anti-mining groups could not possibly give to the islanders. On the other hand, the anti-mining groups never ceased to call for the cancellation of the mining permit of LPI. They did this through mass protests, press releases, fora and symposia in various schools and universities around the country. The spillages aided and bolstered the cause of the anti-mining groups and these incidents were presented as telling proofs and logical reasons to stop the mining operations in the island.

The bond that ties the two sides (LPI and anti-mining groups) is the island and their goal and view of it. LPI wanted to exploit the mineral resources of the island while the local church and its parishioners wanted to protect and save the island from the exploitation of LPI. Many of the anti-mining group members particularly the elders have established a strong attachment to the island, and they see the mining operations as threat to this attachment. LPI has hired some locals to work for the mine. These locals, in turn, become supporters of the mining operations. Many of the anti-mining group members benefit from the projects of LPI and they even have relatives and friends working in the mine. In an island like Rapu-Rapu, things become small and everyone is almost connected to everyone.

Sources

The strong attachment to the island of the local church and its parishioners (relationship conflict-strong emotions), anti-mining groups’ persistent calls for the stoppage of mining operations to save the island (value conflict-exclusive valuable goals), insecurity of the locals on their livelihood and resources (structural conflict-unequal distribution, ownership, control of resources), LPI’s decisiveness to continue the mining operations by continued “buying” of locals’ support with its vast and deep financial resources (structural conflict-unequal power), and government’s dubious plan on the environment (data conflict-different views on what is relevant) have contributed to the conflict as sources of it.

Issues

As mentioned earlier, the main issue stems from the divergent goal and view of LPI and anti-mining groups on the island. Again, LPI is bent on exploiting and extracting the mineral deposits of the island while the anti-mining groups are determined to protect the island from extractive and destructive activities such as mining. Another issue is how LPI lured other locals to support mining by the use of promises, jobs, social services, infrastructures, and access to cash income.

Parties

The primary parties that have direct interests in the conflict would be LPI and the anti-mining groups. Those that have indirect interests would be the mining workers and their families, the state and its DENR, local government units, and other locals of the island. The tertiary parties that have distant interests would be the environmentalist groups and business groups represented by Chamber of Mines of the Philippines.

Attitudes/Feelings

Both sides (LPI and anti-mining groups) exhibited distrust, bitterness and disdain towards each other especially from the anti-mining groups. This probably had something to do with frustration-aggression theory. As goal-oriented, the two sides have continued to frustrate and block each other from achieving their goals (Karbo 2007)[1]. Although the situation did not erupt into violence, but when LPI started to operate, it hired security guards not coming from the locals but from outside the island. It must have figured out that to depend its security on the locals posed a greater risk than having no guards at all. This situation was interpreted by the anti-mining groups as distrust of LPI on the locals’ ability to perform their assignment. However, when LPI implemented various projects for the communities, the anti-mining groups treated these projects as bribes and insincere gestures. When the unfortunate spillage incidents occurred, there was a growing disdain and bitterness among locals particularly the anti-mining groups towards the culprit, LPI. For a time, the incident deprived them of income from the sea and made them insecure of their basic human need of food.

Behaviour

There was a sort of conflict spiral model right after the spillages. The anti-mining groups sent press releases to the media to inform the public of what really happened. LPI tried to downplay the extent and reach of the anti-mining press releases by issuing counter-press releases emphasizing that things were under control and the incident was limited and contained to certain small areas only. LPI even accused the anti-mining groups of sabotaging their desire for truth by releasing to the public and media “unscientific” investigations of the incidents. The anti-mining groups however pressed for an independent investigation of the incident to pin LPI of its culpability and negligence and project LPI and its mining operations as environmental disaster.

Intervention

The DENR as the state’s line agency tasked to oversee and regulate mining activities in the Philippines did commission an investigation by a third party to get to the bottom of the incidents. However, the anti-mining groups and some sectors of society doubted the credibility and objectivity of the investigation. This caused the President to issue an administrative order creating a presidential fact-finding commission chaired by a Catholic bishop to look into the incidents. Both sides (LPI and anti-mining groups) were amenable to the presidential fact-finding commission as they cooperated on its proceedings.

Outcome

The findings and recommendations of the third party investigation and presidential fact-finding commission were given little regard by the state that created it. The DENR slapped LPI 10.7 million pesos in penalties and fines due to obvious violations of environmental laws. Even though the presidential commission recommended the permanent closure of the mining operations, the state through the DENR granted instead LPI to proceed with its full resumption of mining operations after 16 months of the incidents.

Conclusion

What was the use of creating a presidential commission if its findings and recommendation would not be considered or taken into account? The conflict between LPI and the anti-mining groups and the spillage incidents seemed to have unearthed a greater threat to environment – state’s ineptness to use of power and resources. Despite the clear violations of environmental laws, LPI’s apparent disregard of the island’s fragile ecosystem, and the persistent calls for the cancellation of mining permit from the commission, various NGOs, POs, and cause-oriented groups, the state simply slapped LPI with fines and penalties and ordered it to resume its full operations as if little and very minor things had happened.

If nation-state remains to be the most powerful entity that can enforce environmental security (Hamid 2007)[2], how to engage this kind of state on environmental governance will be a major challenge for development and peace workers like us.

References

Abdalla, Amr. et. al. 2002. Understanding C.R. SIPABIO: A Conflict Analysis Model. p. 44-51.

Brown, Oli. 2005. The Environment and our Security: How our understanding of the links has changed. IISD: http://www.iisd.org. pp. 1-7.

*Hamid, Mahmoud. 2007. Lecture Power—Point Presentation on Environmental Security for the students of University for Peace.

*Karbo, Tony. 2007. Lecture Power-Point Presentation on Theories on Conflict and Violence for the students of University for Peace.

http://external.adnu.edu.ph/Centers/CCD/rapu-rapu/rapu-rapu01.html. Date accessed 3 September 2007.

http://www.mgb5.net/3RD-party.htm. Date accessed 3 September 2007.

http://www.mgb.gov.ph/miningissues/rapurapu/issue_rapurapu.htm. Date accessed 3 September 2007.

[1] Based on Dr. Tony Karbo’s lecture on theories of conflict and violence, 2007.

[2] Based on Dr. Mahmoud Hamid’s lecture on environmental security, 2007.

No comments:

Post a Comment