Talk delivered on the occasion of the

National Mining Conference:

Upholding the Integrity of Creation and the Sanctity of Indigenous People’s Rights in the Philippine Context

4-5 February 2008

Government – from the Congress that gave us the Mining Act to the Executive Branch that so eagerly implements it and the Judiciary that as brazenly upholds it – forms one side of the divide.

On the other side is the Church: define her in any way you want, the Church as institution, the Church as people and their many manifestations in civil society, the Magisterium – Pope and Bishops together, or Bishops alone in each diocese and as a group, Bishops with their authority and Religious Orders with their charisms in an agreed-on Mixed Commission (if that still exists, following the “Decree on the Renewal of the Religious Life" of Vatican II and the Guidelines for that Decree supplied in the Document "Mutuae Relationes."). The Second Plenary Council of the Philippines encouraged cooperation between bishops and religious – not that there is a great need for that now as much as in the days of the Martial Law Regime when left-right ideologies tended to make relationships between bishops and many religious often tenuous and uneasy.

No, in the current collision course within the Philippine State between Government and Church, in the area of mining, the Church is, today, hardly fractious in character. She is united and quite tenacious.

The Church, on the other side, talks of morality, of ethics, of what is right and wrong - not only describing what is, but prescribing what ought to be. In the area of mining, what the Government calls legal, the Church denounces as immoral. We have here a situation reminiscent of the early Christian era during the late Roman Empire when both Western and Eastern Church leaders denounced Roman law as immoral, unjust, as it applied in thought and practice to the absolute ownership of Earth by a few for the benefit of a few and the destruction of Earth, in violation of the integrity of creation and the intention of the Creator – almost two millennia before modern scientists caught up with the major living faiths in observing that the Universe had a beginning (13.7 billion years ago), has a continuing story and humans better understand what it is all about.

From the Church’s viewpoint, what is legal is a matter of factual contingency. It is another thing to determine whether the human legal arrangement is just. If it were to be unjust, said

The early Christian philosophers led by St. Augustine’s teacher, Saint Ambrose, quondam Governor of Milan when that post practically meant acting as Chief Executive of the Roman Empire, and later Bishop, warned the “capitalists” of his time that mining should, first of all, follow the “tantum…quantum” (so much…as much) principle, formulated a couple hundred years earlier by Clement of Alexandria: mine only what you need of the earth’s finite non-renewable wealth. There ought to be, as always, a proportionality of means and ends.

Going to present-day times, the former Chairman of the Rapu-Rapu Commission, who is both a Bishop and a Religious, Most Rev. Arturo M. Bastes, SVD, DD reminded us that last week, January 29th, marked the 20th anniversary of the CBCP Pastoral on Ecology that came to be more popularly known as the Letter that asked: WHAT IS HAPPENING TO OUR BEAUTIFUL LAND? In answer to that question then, the Bishops of this country said:

“… (O)

That was twenty years ago.

Less than three years ago, Bishop Bastes said, the President of the

Also appointed to the Commission with Bishop Bastes was Bishop Jose Rojas, DD, of Naga. Bishop Rojas contributed greatly to the discussions on the moral dimension of mining. At the outset, he urged, it must be recognized that mining is not just purely an economic or just a legal issue. It is primarily an environmental issue and as such, it must be governed and justified within the context of environmental ethics or what is now called geoethics.

Etymologically, of course, the word refers to “the ethics of the Earth” – to what is right or what is wrong in any human activity affecting the one planet where we move and live and have our being.

In the course of economic development and growth, many human acts can be either right or wrong relative to their effects on the house of life we call the environment. Human acts are rarely value-free or ethically neutral. They are always either right or wrong. And when they are wrong – no matter what great profits they had brought to some corporations, or revenues to some governments, and prosperity to some individuals and social sectors – if and when those human activities we refer to were essentially wrong, they ultimately and inevitably would have to bring worse problems and deeper crises, for truth is one: the truth of science, the truth of economics and the truth of ecology are one many-sided, non-conflictual truth.

For instance, a certain way of exploiting some mineral resources could bring irreparable, and therefore irreversible, damage to the environment. Any damage to the environment in this way can in turn bring irreparable harm and injury to human health. The dramatic example of the Minamata disease in

Another fact is the non-renewability and non-inexhaustibility of mineral resources. Once they are depleted, there is no way that they can be replaced or restored. We know, as many scientists have pointed out, that the essential resources upon which our global progress depends are not inherently and exclusively created by human ingenuity and technology. On the contrary, the essential resources upon which global progress depends are inherently natural in origin so that resources are fundamentally in limited supply.

Putting it another way: our technological systems and we humans exist within and are subject to the rules and processes of the ecosystems of the natural world. It is not the other way around. We are a part of and not apart from the natural world. Nature does not exist within a human-made and manipulated landscape. The biology of natural systems simply does not function subject to our rules, economies, and decisions. In other words, it is we who exist within and are subject to the natural setting. The natural world does not exist within and is not subject to human artifice.

A given mining operation, therefore, will have to be viewed by people and Government according to this perspective and first be evaluated as either ethically right or wrong, good or bad, before it could even be considered legal or illegal, before it can be judged economically profitable or non profitable, before it can be tested as socially acceptable or not. Without a full respect for the principles of geo-ethics, the exploitation of mineral resources can be very dangerous indeed.

From the very outset, then, the objective of any country that seeks to derive any good from the mining industry should be to ensure that mining is done the right way. In fact, underlying any mining law and the economics that appertain to it should be a solid geo-ethical foundation – a foundation of rules for the use of mineral resources, which are designed to protect people against environmental catastrophes.

Having said that, you will all begin to agree that scientists, great as they are, have a great responsibility as well to work with social philosophers and moral theologians and steer public policy and debate on the uses of the scientific knowledge they come upon. This was a beautiful thing that happened during the work of the Rapu-Rapu Fact-Finding Commission. It’s not just that the Commission Report speaks for itself, but that so many scientific fora and colloquia organized after the Report was made public delved even more deeply into the crucial issues and with more participation from a greater number of our nation’s active scientists.

Never have so many scientists worked together so selflessly and humbly, searching for the truth with pure hearts and love of country, and in the end coming to an unprecedented consensus of caveats on mining in a small island ecology with steep slopes, against the on-going threats of acid mine drainage and insufficient dam integrity – all of which, parenthetically, were lauded and agreed to by the Government’s DENR but whose conclusion and urgent recommendation for mining moratorium in Rapu-Rapu were so illogically cast aside by the same government agency that earlier became so famous for so much mea culpa and mea maxima culpas in the Lafayette mining tailings spillage of 2005 October to 2006 February and a few more times thereafter.

The constant insistence of Bishop Bastes before media that the ethical approach that the investigative commission had taken was meta-scientific and meta-legal, or – in simpler terms – beyond and beneath the purely scientific and the purely legal angles, got chewed on and constantly chewed out by shameless propagandists – including one of the Australopithecus type like Mr. Peter Wallace – who mercilessly twisted this Bishop’s alleged confession of the “unscientific” methodology of the commission that he headed.

Wallace would have the temerity to repeat like a mantra, Hitler-like, the line that the Mining Act which so many of us seek to review is the best mining law in the world, while immediately hiding with malicious glee the enthymeme that yes, it is the best in the world for their interests, from their point of view.

We understand their tack: they believe that constant repetition might just turn their lie into a “truth”. And we … we really only have ourselves to blame when our hospitable traits are taken for weakness and illiteracy, when the consultants we take for our internal discussions of the precise meaning of our Constitution’s provisions on the national patrimony are not our own national but unabashed Australian interest defenders, even as we smile with patience at their grossly utilitarian standards and their shameless assumptions that what is good for them are what is good for our country as a whole.

The 1960’s song echoes in my ears, “Oh when will we ever learn, oh when will we ever learn?”

Imagine that a foreign corporation arrived one day with your national government’s blessing and seized your home; destroyed your local store, local farms and gardens, your church, your favourite park; polluted your drinking and bathing water; created hazardous waste dumps throughout your town; blocked your efforts to seek justice through the courts; and bankrolled the police who threatened, tortured, raped, and killed family and friends for trying to resist this destruction of your way of life, promised your local government more revenues and then twisted the arms of some national agencies to give it more tax holidays than the total duration of the mining operation. Would you not say that you had a few serious ethical questions in your hands?

Not the Bastes Commission in Rapu-Rapu but the United Nations, and international and local NGOs have independently identified the following human rights abuses associated with an increasing number of mining operations and which the CBCP as a body is so concerned about. You would have been hearing a lot about this since yesterday:

· Torture, rape, indiscriminate and extra judicial killings, disappearances, arbitrary detention, employment discrimination, interference with access to legal representation, and severe restrictions on freedom of movement;

· Violation of subsistence rights resulting from seizure and destruction of thousands of hectares of forests, including community hunting grounds and forest gardens, and contamination of water supplies and fishing grounds;

· Violation of cultural rights, including destruction of sites held sacred by indigenous peoples; and

· Forced resettlement of communities and destruction of housing, churches, and other shelters.

And yet, to be fair, we must make mention of the fact that there is an Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, founded in 1893 and incorporated by Royal Charter in 1955, which includes an assemblage of scientists, engineers, technologists, geologists and other geoscientists, mining engineers and metallurgists, also other professional and para-professional groups who are engaged in or associated with the industries; and students who are preparing for careers in the industries, all of whom have committed to and are required under their Bye-law 30 to comply with their Code of Ethics and with the Code for Consultants when practicing as such. Down under, not all are as wild and irresponsible as Wallace – consultant to Philippine governments, think-tanks and newspapers.

It may suffice to underscore the very first rule, which they explain and we hereunder quote at length.

“The responsibility of members for the welfare, health and safety of the community shall at all times come before their responsibility to the profession, to sectional or private interests, or to other members.

“The principle here is that the interests of the community have priority over the interests of others. It follows that a member:

a. shall avoid assignments that may create a conflict between the interests of his client or employer and the public interest;

b. shall work in conformity with acceptable technological standards and not in such a manner as to jeopardize the public welfare, health or safety;

c. shall endeavour at all times to maintain technological services essential to public welfare;

d. shall in the course of his professional life endeavour to promote the well-being of the community. If his judgment is over-ruled in this matter he should inform his client or employer of the possible consequences (and, if appropriate, notify the proper authority of the situation);

e. shall, if he considers that by so doing he can constructively advance the well-being of the community, contribute to public discussion on scientific and technological matters in his area of competence.”

When you read such lines in a Code of Ethics subscribed to by Australian firms, you should not be faulted if you start wondering whether they have isang salita or whether they have, in fact, a double standard of behaviour – one for the home front and another one for investments abroad. Would they do or not do in their home countries what they so easily do or not do in our country? Again, we Filipinos would have no one to blame but ourselves if we did not know any better, if we so easily take as gospel truth the grandiose pronouncements of foreign propagandists, especially the ones we so hospitably allowed to infiltrate our society and many of our officials’ thinking on matters of patriotic concern and national interest.

The Bastes Commission Report remarked that people of earth have a duty to govern the world with justice and harmony even as they use for themselves all the earth and all that it contains. Church leaders are not – they could not be against mining per se. Mining has been an important part in the historical development of civilizations – from first (agricultural) to second (industrial) to third (information) wave of social formations.

Industries need minerals to support the production and flow of basic goods and services. The production and availability of a broad range of metals are essential to modern life. Throughout human history, economic progress has been dependent to a large extent on the availability and use of metals. We agree with the observation of the International Council for Mining and Metals that, given their unique physical and chemical properties, metals are essential for a number of uses – in transportation, housing, power generation and transmission and electronics, as well as for a wide range of high technology applications in the telecommunications, computer, and aerospace, medical and environmental control industries.

We especially note their acknowledgement that metals can be reused and recycled indefinitely without loss of their properties.

In any case, how fortunate should our country have been, given the mineral resources vital for industrialization! As noted in the Bastes Report, the Philippines is a part of earth that is so incredibly rich in gold, silver, copper, nickel, chrome and zinc that there is now a consensus among governments and industry in the valuation of the mineral wealth within the territorial limits of our country at more than a trillion dollars’ worth, at least. The problem, however, has been – again – the fact that the Philippine Government and the Filipino people do not really own and control mining as a crucial part of basic industry.

In geo-ethical terms the State and the Filipino people have to date not actively subscribed to the fundamental geo-ethical principle of stewardship. Stewardship, in general, means the protection, care and proper use of this world’s resources.

According to the Principle of Stewardship, human beings are called by nature to nurture, protect, use, order, and adorn the earth and all living and nonliving creatures in harmony with and obedience to the fundamental laws written into the very nature of all things. Thus, the steward is more a manager, and not an absolute owner.

In this era of rising consciousness about the physical environment, we humans are called to a sense of moral responsibility for the protection of the environment. And the State and the Filipino people are likewise called to care for the special environment and biodiversity they have been gifted with, including all the natural wealth and mineral resources of the Philippine archipelago – in short, to be responsible as stewards for the national patrimony towards the attainment of the common good.

As stewards, the State and the Filipino people must be able to effectively impress on miners the importance of responsible management of their operations from discovery to closure, contributing to the scientific knowledge regarding the safe production, use and disposal of metals. Past mining methods have had, and methods used in countries with lax environmental regulations continue to have, devastating environmental and public health effects.

And, of course, no matter how huge the mineral deposits, they are finite. Wouldn’t the mineral resources run out soon enough on account of their being limited, given the unregulated corporate greed to control every significant mineral vein in the country? Shouldn’t we rather develop our own basic and medium industries to ensure we have enough wherewithal for industrialization? As stewards, Government and people are responsible for furthering the task of building a strong industrial economy. They must not give up on the possibility of seriously developing in our country an integrated mining industry.

There is room for foreign investments – room. It is crazy to give them the whole house. That would be tantamount, again, to giving up on the stewardship obligation and vocation.

What we need is a strong state that can rigorously screen and strictly regulate these investors and amend the Mining Act to include the crucial provision of the Government's pre-tax share of the cash flow generated by a mining project. In most countries around the world where there is mining this pre-tax share representing the national patrimony averages a hefty 38% (Chile 15.00%, Bolivia 27.06% ,Venezuela 32.82% ,Peru 36.52%, United States 36.61%, Mexico 37.21%, Botswana 40.10%, Brazil 40.85%, Argentina 46.13%, Canada 46.71%, Guyana 48.16%, Australia 50.60% )! In the

At the present time, the Mining Act is blind on how the State – which has the exclusive duty to explore, develop and utilize natural resources – would participate in the profits of service contracts such as financial and technical assistance agreements with mining contractors. The law also does not guarantee that the government will receive an equitable share on the mining contractor's profit. The government's share in the mining deals only includes taxes, duties, and other fees paid by the contractors.

The payment of these fees does not immediately benefit the Philippines as the contractors are given the privilege of first fully recovering their pre-operating and property expenses before paying their financial obligations to the government, not to mention the aggressive grant of tax holidays to foreign investors in mining, which does not make sense at all since mining is that kind of investment which is neither market-seeking nor efficiency-seeking so much as clear asset-seeking.

The

In essence, with a strong state and a people who understand the principle of stewardship, mining projects that cannot absorb the environmental and social costs of modern mining should not be allowed to proceed. Period. Then we won’t have the case of a

Stewardship understood in this way means primarily the preservation and conservation of nature. However, it does not in any way preclude the creative transformation of nature, represented by human ingenuity and technology. In performing this task, however, human beings must recognize that they can only proceed within a certain limit and that the resources with which they must work are not necessarily inexhaustible.

Thus, stewardship – to the chagrin of many businessmen - is not a license for doing just about anything or for trying out anything just because it is possible. Rather it entails more than anything else, restraint and responsibility in the use of this world’s resources. No matter how human beings may progress in science, freedom, and power, they should not dare abuse this responsibility and in the process contradict their own human nature with the consequence of destroying themselves and their environment.

Nature is to be creatively transformed but not to be relentlessly exploited. The slogan should be “Need rather than greed.” We will not encourage people to be simply driven by the desire to satisfy wants and wantonly engage in research and experimentation without taking into consideration risks and negative consequences.

So when is mining an exercise in responsible stewardship? We can sum up the sense of our common teaching thus:

1. When the site on which mining is conducted is suitable, that is, one that has low permeability foundations, and a stable geomorphic environment.

2. When, in the process of mining, the ecological balance is not destroyed so that there is no harm to essential biodiversity; the air and the water are not contaminated by toxic wastes (there is strict enforcement of pollution control measures); there is no serious harm and injury to human health.

3. When social justice is served: the main benefits of mining redound to our country, and particularly local communities, and not exclusively to foreign mining interests; our nationals are given preference in the employment of personnel; taxes due to the government are paid honestly by the mining company; the working conditions are healthy and safety measures are in place, and all kinds of necessary insurance for the physical well-being of the workers are provided; just wages and benefits required by the labor code are given by the mining company to their employees, including bargaining agreements and recognition of their right to strike.

5. When cultural values are not sacrificed under the guise of development, i.e., the industry does not conflict with traditional cultures which are in harmony with nature.

6. When ancestral lands are not expropriated without just compensation, or in utter disregard for religious sensibilities.

7. When extreme care is taken to prevent or at least minimize the risk of serious accidents, as the damage to the environment or human health could be irreversible. It is necessary to create instruments for monitoring and controlling both local and transnational operations with mineral reserves which might result in heavy dangers for the life of future generations.

8. When population displacement engendered by mining operations, if necessary and inevitable, is delicately managed through humane and equitable relocation, and better conducted without physical force and violence, as much as possible, but rather in the context of reasonable and peaceful dialogue.

9. Most of all, when the “advantages” that are envisioned by such exploration and exploitation of nature are not to be confined to only a few but reach the majority they are meant to benefit.

We need to underscore the present situation in our country that needs to find new ways of thinking and new ways of planning and controlling mining activities. A considerable improvement of ethical climate is needed and hopefully some of the principles of geo-ethics discussed here will go a long way to helping in dispelling muddled thinking and giving new clarity of direction. It is not always easy. What happened in Rapu-Rapu is quite instructive.

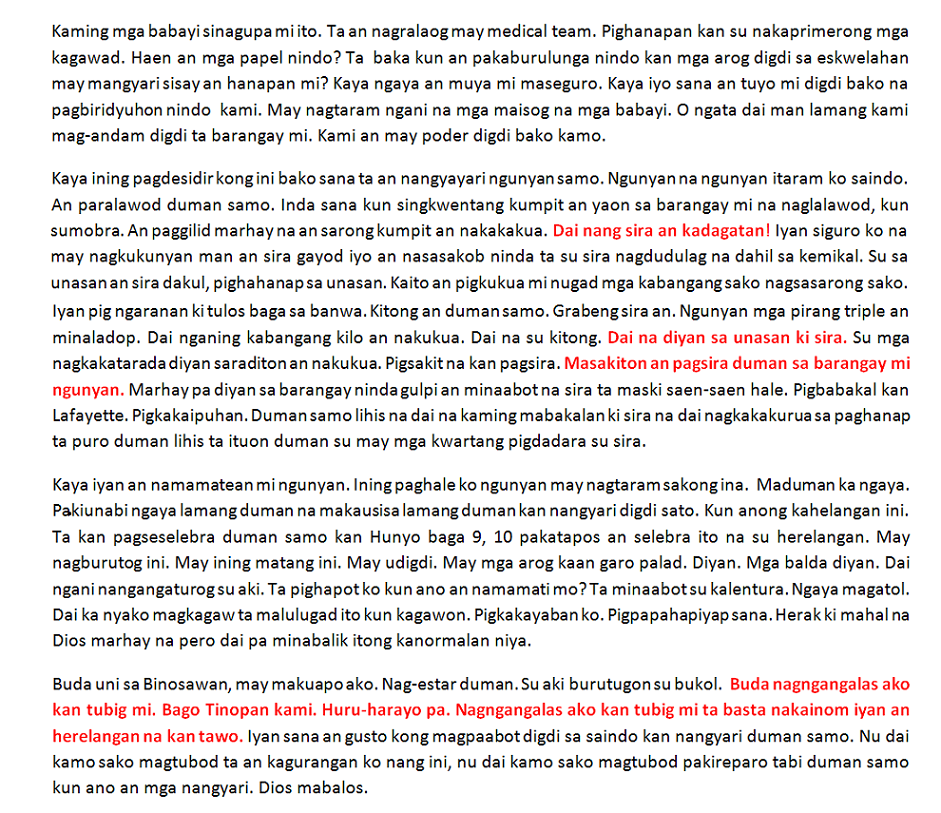

The Bastes Commission had earlier established that "

The Rapu-Rapu mining project had met with fierce resistance from local communities since its inception, with concerns centred on:

· Inadequacy of environmental and social impact assessment process;

· Exposure to typhoons, as the island was quite in the centre of the typhoon belt and heavy rain area;

· Serious toxic spills in the past and related findings of negligence and breaches of basic industry practices;

· Unresolved community impacts and questionable social acceptability as reflected in widespread opposition to the mine;

· Direct and long term environmental impact of the mine, in an island of steep slopes, through Acid Rock Drainage, toxic discharges, long term solidity of tailing dam design, direct impact on island and aquatic biodiversity;

· Effect on emerging ecotourism industry based on whale shark watching;

· Undue pressure on local government structures and citizens’ rights.

The government through the DENR should really just have followed the rule of law rather than the culture of privilege and impunity. The government that often prides itself in underscoring legality sometimes can be quite selective in its utterance. In accordance with the spirit and letter of the law, DENR should just have cancelled the Environment Clearance Certificate (ECC) of a recidivist firm, and if allowed to re-apply, let it undertake the drawing up of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and propose an Environmental Management System (EMS), precisely as the law requires, and then let an awakened citizenry watch a reformed DENR do its job. That is what the Bastes Commission logically recommended which the DENR so illogically ignored – even as they both argued from and agreed on the same major and minor premises.

In addition, the Commission found strong indications to believe that the firm underreported its production of ores and of processed gold and silver to the MGB or Mines and Geosciences Bureau thereby reducing the basis, and ultimately, the value of the excise tax they would have to pay the government.

Bastes warned that Lafayette only wanted to have DENR hostage in their threat that if their mining permit or ECC were cancelled, they’d just walk away and leave DENR with the mine tailings and the pollution and the crisis. And DENR was just too weak to defend the environment and people’s health and welfare. It surrendered, in the name of attracting more investments – of the credit card variety. This is the type that brags, “Have permit and there will be banks to give you a credit line.” During the term of Secretary Reyes, the state was clearly captive. He could not withhold the mining permit that

Now the

And has the important lesson been learned? A company that fails to obtain and retain a social licence to operate, in other words one that operates without community approval, is simply not viable – even if one has the Reyeses’ and whole armies’ arbitrary license to be illogical and insane, as clearly happened in the Lafayette Rapu-Rapu experience.

These are not the best of times. The world demand for our minerals is at a new high. And Government is at a new low - easily held captive by the transnationals, and so weak and so unwilling to put people's welfare and environmental conservation above the fetish of investment promises that become a source of even greater frustration all around. These, however, are the most challenging times. Can't a new combination of bishops and religious people succeed in forming enough numbers of the lay faithful so that the latter can seriously start transforming the world? Thank you very much and good day!

No comments:

Post a Comment