http://mensab.wordpress.com/2007/10/23/rapu-rapu-mining-issues-and-advocacy-campaigns/

After the Brundtland Report of 1987 and the Earth Summit of 1992, the rhetoric of development planning and intervention has been sustainable development. Its basic principle is meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising those of the future generation, and in the process improving the quality of life.

In the Philippines, this premise was articulated in the Philippines Agenda 21 (PA 21) which “envisions a better quality of life for all Filipinos through the development of a just, moral, creative, spiritual, economically vibrant, caring, diverse yet cohesive society characterized by appropriate productivity, participatory and democratic processes, and living in harmony and within the limits of the carrying capacity of nature and the integrity of creation.” PA 21 had extensive influence and tenor on the policymaking and policy direction initiatives which deal toward the quest for sustainable development.

RA 7942: Pro-people and pro-environment?

The passage of Republic Act (RA) 7942, otherwise known as the Philippine Mining Act of 1995, is said to be a step forward to that quest. Although many critics of the new law would call for its repeal due to the apparent surrender of our mineral resources for their exploration, utilization and development to foreign-owned mining companies, many were also satisfied with the restrictions and regulations put in place to secure the welfare of the host communities and the minimum impact on the environment of mining operations.

Since the mining industry is often blamed for many environmental catastrophes, such as tailings spillages in Marinduque and Sipalay, Negros Occidental, the paradoxical “sustainable mining” is introduced by the industry to counter the pessimistic perception and negative image of mining as extractive and destructive. Likewise, the DENR revised the Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of RA 7942 to project mining as pro-people and pro-environment. Operationalizing sustainable mining though faces serious doubts on its feasibility and expediency. Land rehabilitation in the post mining stage and best practices in mining industry’s environmental management are dependent on the strict implementation, monitoring, evaluation of the DENR and actual compliance of the mining companies on the conditionalities of the Environmental Compliance Certificate (ECC) issued to them. This is where the DENR fails to appease the critics and anti-mining advocates on its capability to implement and carry out environmental laws that protect both the people and environment.

What is novel in RA 7942 is the social acceptability clause that is required in any mining projects. No ECC will be issued if the locals oppose the mining project being proposed. In other words, it’s the decision of the locals which can make or break a mining project.

Rapu-Rapu case

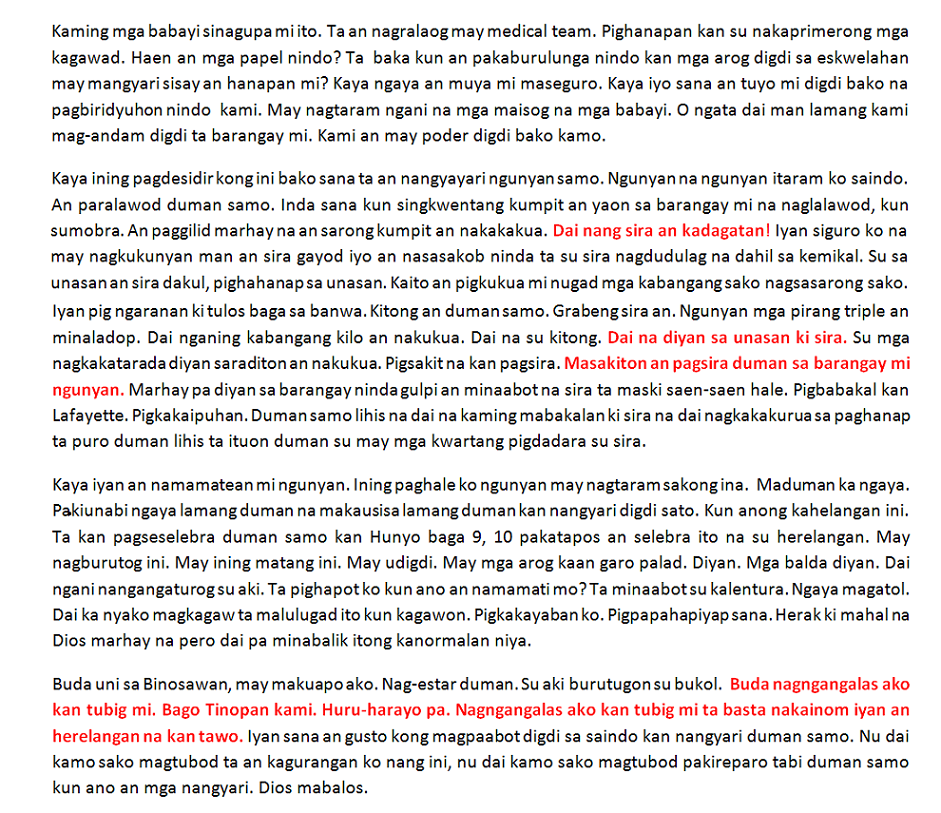

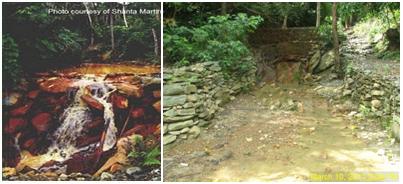

In July 2001, the DENR granted an ECC with 29 conditionalities to Lafayette Philippines, Inc. (LPI), an Australian mining company, on its Rapu-Rapu Polymetallic Project. Lauded as the first mining project to undergo the rigorous process of acquiring the necessary requirements set by RA 7942 leading to the issuance of ECC, LPI intended to mine gold, silver, copper, and zinc in Rapu-Rapu Island, Albay for six years. In granting the ECC to Lafayette, the DENR was convinced that the project was able to muster necessary and sufficient support from and was socially acceptable to the locals. This view was disputed by Sagip-Isla Sagip- Kapwa, Inc. (SSI), a people’s organization established through the initiative of the Rapu-Rapu parish to campaign against mining the island. SSI was supported by various religious congregations headed by Bishop Jose Sorra of the Diocese of Legazpi, cause-oriented groups, and the three major universities in Bicol, namely, Ateneo de Naga University, Bicol University, and Aquinas University. Despite the support of these institutions and groups for the anti-mining campaign, the DENR saw that majority of the locals were in favor of the conduct of the mining project in their island.

Surprisingly, the issuance of ECC to Lafayette came at a time when resistance to mining was widespread and gaining popular support. It was at this time when the people of Mindoro through the Alyansang Mindorense (ALAMIN) rejected the mining project of Mindex/Aglubang Mining Corporation which led to the cancellation of the DENR of the Mineral Production and Sharing Agreement (MPSA) with Mindex/Aglubang. Earlier cases of resistance to mining had happened in various places where mining projects were threatening to happen or operating. The Subanen in Western Mindanao demanded to revoke the exploration permit of Cozinc Rio Tinto Ltd. of Australia (CRA), a subsidiary of Rio Tinto Zinc (RTZ) of Brazil (Tujan and Guzman 1998, 178), In Siocon, Zamboanga del Norte, small-scale miners barricaded the mining area of the Canadian Toronto Ventures, Inc. (TVI) to stop its operations (ibid., 162-163). Barricade was also put up by the locals of Itogon, Benguet when they protested the open-pit mining project of Benguet Corporation which resulted to the suspension of the project operation in the area (Caballero 2001, 176).

So this paper asks, what happened with the advocacy campaign against mining in Rapu-Rapu? What lessons could we glean from Rapu-Rapu advocacy experience?

Lessons from Rapu-Rapu

Several lessons could be learned from the advocacy campaigns launched by both pro-mining and anti-mining groups as they tried to influence the decision of the locals whether to resist or accept the Rapu-Rapu mining project. First, advocacy campaigns must be grounded on, sensitive and responsive to the realities of the locals. The pro-mining advocacy campaign was able to highlight the locals’ basic need – a regular source of income. Many locals were not earning sufficiently from fishing and farming. They were looking for alternative source of income which the mining project could provide them. Aside from that, another factor that could have tipped the scale in favor of the mining project was the timing of the project. In October 1998, super typhoon Loleng raged the province of Albay which brought devastating damage to properties especially houses of the locals. Understandably, the decreasing fish catch and unreliable crop production in the area did not help much in providing cash income for the repair and construction of the houses. Many locals who wanted to have access to cash saw the mining project as an opportunity to have their houses repaired and rebuilt and to gain a regular source of cash income.

Second, leadership is key to a successful campaign. The pro-mining group found influential and effective leaders in the politicians and public officials in Rapu-Rapu, while the anti-mining group was unable to find leaders in important areas such as the direct impact barangays of Malobago and Pagcolbon. In barangay Binosawan however, the anti-mining group found good leaders that’s why Binosawan remains a stronghold of the anti-mining group in Rapu-Rapu.

Third, the organizational structure of a group and its capacity to strategize the advocacy campaign are effective when they involve the local leaders and capitalize on the present needs and vulnerabilities of the locals. The pro-mining campaign was backed by a clear-cut organization (LPI) with substantial funding and full-time staff focused on convincing the locals of the benefits and advantages of the mining project unto their lives, while the anti-mining group was driven by a loose organization composed of volunteers. Although these volunteers who were mostly teachers, students, professionals, fishers, and farmers seemed passionate of the cause, they still needed to attend to their primary jobs outside of struggle against mining. Also, the structure of SSI was concentrated and attached to the parish structure that when the priest transferred to another assignment, the whole campaign got affected and took a backseat.

Fourth, strategies that encourage and entail local participation in campaign activities create a sense of belongingness and ownership of the struggle. The wider the reach or contact of the activities among the locals, the greater the chance the locals will participate. Marvic Leonen (2000) cites the challenges confronting advocacy, and on top of them is to identify a constituency. It is “the problem of whom one can represent as an advocate and of what one can legitimately say on the basis of the sector, class, or group represented” (ibid., 81). It should be clear who the target constituents of the campaign are. The pro-mining group was bent to get the approval of the public officials first, then it worked from there going to the level of the locals with the local leaders’ blessing and sometimes with the local leaders’ presence in the campaign. As in other rural area, the patron-client relations still dominate the political, economic and social landscape of Rapu-Rapu.

Fifth, simplicity and clarity of the message and content of advocacy campaigns generate understanding, response and ultimately acceptance. Clearly, the message of pro-mining group was employment and various development projects, such as electrification, school building, livelihood projects, among others, while SSI conveyed the goal of avoiding the impending destruction of the island’s ecosystem once mining operations commence. Unfortunately, this was not quite intelligible to the locals, especially if expressed through figurative and metaphoric forms in the homilies or sermons of a priest.

Sixth, the role of media cannot be undermined in advocacy campaigns. Both pro-mining and anti-mining groups had relative successes in disseminating and raising their points and counter points for and against mining through the use of media. The anti-mining group was able to call the attention of the Senate through its Committee on Environment to conduct an inquiry in aid of legislation regarding the mining issues in Rapu-Rapu. The pro-mining group, on the other hand, took a time slot in a local radio station in Legazpi City, Albay exhorting the public of the benefits of the mining project.

These lessons challenge the way the locals are treated in advocacy campaigns. In various contexts, the locals are situated in a particular environment. To influence their decision, these contexts that enfold their behaviors must be taken into account in the formulation of advocacy agenda. The complexities of the situation on its context present the realities of the locals where an advocacy campaign may start.

Lafayette has just been given a permit to proceed with its test-run after two incidents of spillages that resulted to a fish kill in the immediate fishing areas. Again, the mining company made an assurance that preventive measures which cost millions of pesos had been put in place. This news poses a disturbing scenario where mining companies can justify their position by declaring their huge expenses (but not their income) and by virtue of that huge expense, it deserves to operate again to have a return of investment. This means that the struggle against mining in Rapu-Rapu continues so does the quest for sustainable development. As Tandon (1993) puts it, “resistance today is the main form of sustainable development.”

References:

Caballero, Evelyn. “Strategies of Survival for a Community of Traditional Small-Scale

Miners.” In Towards Understanding Peoples of the Cordillera: A Review of Research on History, Governance, Resources, Institutions and Living Traditions, eds. Victoria Rico-Costina and Marion-Loida S. Difuntorum. vol. 1 Cordillera Studies Center. UP Baguio, 2001.

Leonen, Marvic. “NGO Influence on Environmental Policy.” In Forest Policy and

Politics in the Philippines: The Dynamics of Participatory Conservation, ed. Peter Uting. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2000.

Tandon, Yash. “Village Contradictions in Africa.” In Global Ecology: A New Arena of

Political Conflict. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing, 1993.

Tujan, Antonio and Ros-B Guzman. Globalizing Philippine Mining. Manila: Ibon Books, 1998.

No comments:

Post a Comment