UPR 1st Session, 7th – 18th April 2008

Philippines

Submitted on Behalf of the following Organizations:

Catholic Agency for Overseas Development (CAFOD).

Columban Faith and Justice Office.

Indigenous Peoples Links.

Irish Centre for Human Rights, National University of Ireland Galway . IUCN

Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy. Trocaire.

23rd November 2007

Background / Context of Submission

The extractive industries have been described as having an ‘enormous and intrusive social and environmental footprint’ throughout the world. The UN Secretary General’s Special Representative on the Issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises, Professor John Ruggie, has acknowledged the deplorable record of the extractive industries in relation to human rights violations resulting largely from militarization and corruption. This has led to a broad array of abuses ‘up to and including complicity in crimes against humanity’. He described the extractive industries as ‘utterly dominating’ in terms of reported abuses, accounting for two-thirds of the total reported to him under his mandate. This trend is evident in the Philippines with abuses affecting local communities, especially indigenous people on whose ancestral domains most of the countries mineral reserves are located. This submission focuses on the impacts of the Philippine Government’s current mining plans - which target up to 30% of the country for mining applications - on the human rights of its indigenous peoples and other affected communities.

i) The methodology and the broad consultation process followed nationally for the preparation of information provided to the UPR by the country under review.

The Catholic Bishops of the Philippines attracted international attention because of their concerns regarding the proposed expansion of the mining industry. A fact finding team (henceforth FFT) consisting of the Rt Honourable Clare Short MP and former UK International Development Secretary; Clive Wicks, a Member of CEESP the IUCN Commission on Environmental Economic and Social Policy; Cathal Doyle, a representative of the Irish Centre for Human Rights; and Fr Frank Nally, Columban Faith and Justice Office, visited the Philippines in July / August 2006. The aim of the FFT was to assess reports of human rights abuses, environmental degradation and corruption associated with planned and current mining operations. They met with representatives of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines, a broad range of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), indigenous peoples’ organizations, academics, Senate and House members, the Chairperson of Transparency International-Philippines, a provincial governor, the World Bank, the Under-Secretary of the Department of the Environment and Natural Resources, the British Ambassador, the Chair-man of the Chamber of Mines, the Minerals Development Council, the Chief Justice, and the Ombudsman. The findings were documented in the report Mining in the Philippines : Concerns and Conflicts (Attached). A Working Group on Mining in the Philippines (WGMP) was subsequently established by a number of the submitting organizations. This submission reflects findings of the FFT as well as the on-going research being conducted by the members of the WGMP and their partner organizations.

ii) The current normative and institutional framework of the country under review for the promotion and protection of human rights: constitution, legislation, policy measures …

The Philippines has ratified the major UN human rights treaties. The 1987 Constitution of the Philippines , in line with international law, recognizes and promotes the rights of indigenous cultural communities. It upholds the right to practice their customary laws governing their ancestral domain, guarantees respect for their traditional institutions, which are necessary for the administration and promulgation of same, and ‘recognizes and promotes the rights of indigenous cultural communities within the framework of national unity and development’.

The Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA 1997) was enacted to facilitate compliance with these obligations and requires that the State recognizes their rights to self-governance and self-determination and respects their customary law and institutions. IPRA also requires that where development projects impact on indigenous peoples their Free Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) must be sought ‘in accordance with their respective customary laws and practices’. The right to FPIC extends to natural resource extraction projects. FPIC is defined as: the consensus of all members of the ICCs/IPs [Indigenous Cultural Communities/Indigenous Peoples] to be determined in accordance with their respective customary laws and practices, free from any external manipulation, interference or coercion, and obtained after fully disclosing the intent and scope of the activity, in a language and process understandable to the community. (IPRA Section Chp III 3 g)

iii) The implementation and efficiency of the normative and institutional framework for the promotion and protection of human rights described in ii). …

Indigenous Peoples’ Rights

The Philippines gained international credibility for its legislation on indigenous peoples’ rights, which is in-line with the newly adopted UN Declaration on Indigenous Peoples. However, the FFT heard compelling evidence that indigenous peoples’ rights, in particular the right to FPIC, are being systematically denied in the context of mining on their ancestral lands. The indigenous communities the FFT met raised a number of issues that they claim were serious impediments to the effective implementation of their right to FPIC and resulted in violations of their customary laws, disregard for their institutions and destruction of their sacred sites [i].

Firstly, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) is the body mandated to ‘protect and promote the interest and well-being of the ICCs/IPs’. It is responsible for ensuring adherence to the implementing rules and regulations of the IPRA. The perception among indigenous peoples, based on their experience of the FPIC process to date, is that the NCIP is failing in its mandate. Rather than protecting and promoting the rights of indigenous peoples, it appears that the NCIP is facilitating the entry of mining companies. Some blame this on a lack of funding for the NCIP, others on its lack of independence from a political agenda that is strongly pro-mining; others still attribute it to corruption and bribes by mining companies. They feel that the selection process for its commissioners, which is under the office of the President and not under the control of indigenous peoples, is at the root of its problems.

Secondly, indigenous peoples felt that there was inadequate respect for their traditional cultures. Their right to FPIC was viewed as a technical obstacle to be overcome as quickly as possible. Meetings organized by the NCIP as part of the FPIC process often took place in a location that was not in accordance with traditional customs of the indigenous peoples. In addition the decision making process did not adhere to the requirement that consensus of all members of the community be reached in accordance with customary laws [ii].

Thirdly, and related to the above point, the NCIP guidelines for the implementation of FPIC impose restrictions on the time, manner and process of FPIC, which are not in conformity with the customs, laws and traditional practices of indigenous communities. One of these restrictions is the imposition of restrictive and discriminatory timeframes for completion of FPIC process. The total time now allotted to the conduct of an FPIC process is only 55 days, effectively only allowing in the region of 15 days for community consensus building[iii]. This does not give indigenous peoples sufficient time to conduct their traditional indigenous decision making processes or to consider the wide-ranging implications of mining, thereby eliminating the possibility of taking informed and culturally appropriate decisions about whether to grant their FPIC.

The fourth issue concerns factionalism and misrepresentation. A pattern appears to exist where the NCIP in conjunction with the mining companies attempt to capitalize on, or generate, division within indigenous communities. In cases where the consent of the indigenous people has not been forthcoming, non-representative indigenous leaders have been created and recognized by the NCIP and the mining companies[iv]. Some communities also described manipulative processes including the misuse of attendance sheets as proof of consent and offers of cash or food in exchange for consent[v]. The indigenous people view the selection of leaders through procedures that do not respect customary laws as a violation of their culture, traditions and rights. According to them consent obtained in this manner should not and cannot be the basis of FPIC. This view is supported by IPRA, which requires that consent be obtained ‘in accordance with the customary laws and practices’ and ‘free from any external manipulation’. Cases similar to those recounted to the FFT, where mining companies were involved in engineering consent, have been documented throughout the country.[vi]

Finally, expert or even rudimentary independent information regarding mining is not being made available to indigenous peoples. Rather than being informed about the potential impacts of mining, as required by IPRA, the information they are currently provided to communities appears to amount to little more than promotional material by the mining companies[vii].

Economic Social and Cultural Rights: Rights to Food, Water, Livelihoods and Health

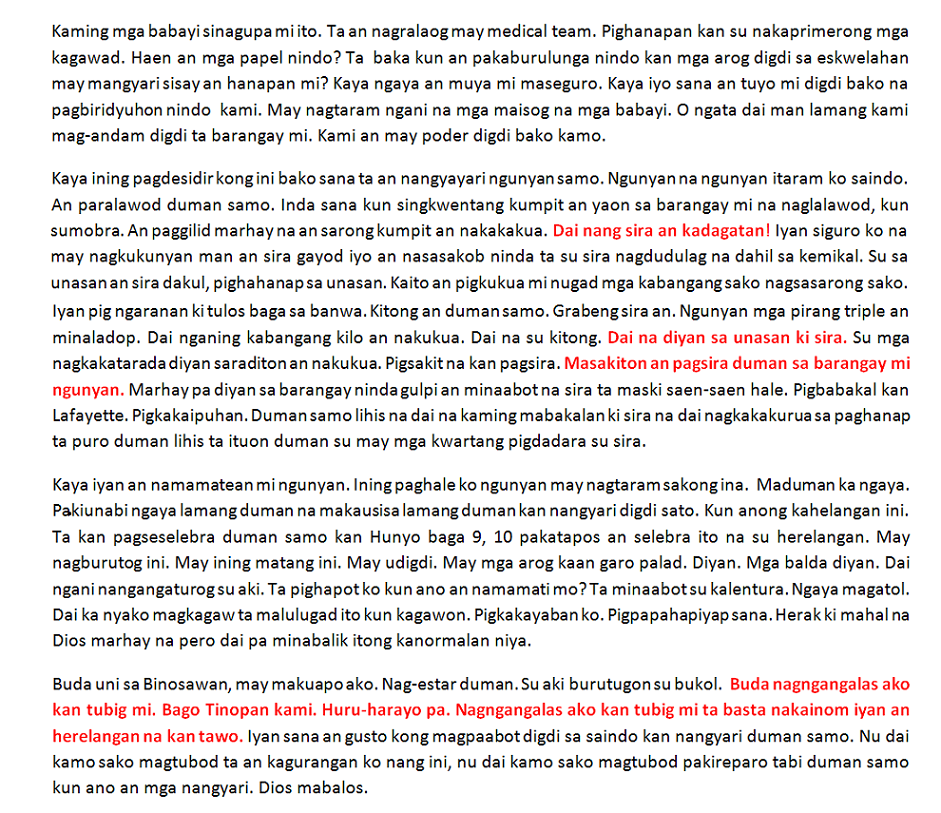

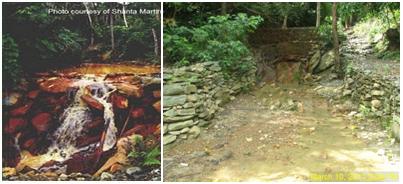

Mining has a poor record in the Philippines as a result of environmental disasters[viii]. The 1996 Mar-copper mine tailings spill, on Marinduque Island , was so severe it resulted in the Boac river being declared biologically dead by the UNEP[ix]. According to locals the effects of the disaster were still having an impact on their livelihoods and health almost a decade later[x]. Spills of cyanide and tailings at the Lafayette mine on Rapu Rapu Island in 2006 resulted in fish kills. An independent commission established by the Government to investigate the spills at the Lafayette mines, found the company guilty of negligence and recommended that the mining operation be closed down[xi]. However, the mine remains open and locals fear that recent fish kills are again attributable to the mine[xii].

This poor record is partly a result of the conflict of interest that exists in the mandate of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). On the one hand it is responsible for the approval of exploration and mining applications and on the other for environmental regulation, monitoring and legal enforcement. While the DENR recognizes that ‘pollution of water sources such as rivers and lakes is evident in many parts of the country’, there appears to be a disjunction between this assessment and its recommendations that 28% of the landmass of the Philippines ‘has yet to be developed’ for mining[xiii]. Those most likely to be adversely affected are indigenous and local communities who rely on agriculture and fishing for their livelihoods and food. The population of the Philippines is expected to grow from its current level of 84 million to over 150 million within 30 years. The countries food security will suffer if agricultural lands, waterways and the seas are negatively impacted by numerous large-scale mining operations[xiv].

Mining can also be a major consumer and a major polluter of water. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, water contamination from mining poses one of the top three eco-logical security threats in the world. In the Philippines , many mining and exploration concessions overlap watershed areas where demand for water exceeds the available supply. Mining in these areas would therefore be likely to compete with the needs of other users, including farmers and house-holds, for scarce water. Many mining sites are located on mountains that act as watersheds for numerous rivers, potentially compounding the threat. The communities and organizations the FFT met with, all voiced grave concerns about the potential and current impacts on the volume and quality of water. Where exploration and mining are in the feasibility stage, local communities fear that pollution and siltation of rivers may deplete water sources. This can reduce rice production and fisheries and have serious health impacts. These concerns are reflected in the documented experience of many communities downstream of existing mines[xv]. The crisis of water management and irrigation has been raised by the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) in the Philippine Medium Term Development Plan 2004-2010[xvi].

The UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food highlighted that indigenous peoples’ right to food embodied the notion of cultural acceptability i.e. ‘sufficient food corresponding to the cultural traditions of the people’[xvii]. Obstacles he recognized to their enjoyment of this right, included, inter alia, lack of recognition and effective implementation of rights to land and resources; lack of control over development projects that impact them, appropriation of resources and a lack of access to justice. In the Philippines , as was the case of the Subanon at Mount Canatuan , mining has also lead to the destruction of indigenous peoples’ sources of medicinal plants fundamental to their culture and well-being

Civil and Political Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities

Right to Life and Freedom of Expression (Extra-judicial killings)

According to Karapatan (a Philippine NGO) and other human rights organizations, more than 800 people have been extra-judicially killed in the Philippines since 2001[xviii]. Many of the victims were journalists, human rights and environmental activists or members of legal political opposition groups. The consensus emerging from organizations that have investigated the killings, such as Human Rights Watch, is that mining activists are among the target groups, with claims made that at least 18 killings were of activists involved in anti-mining protests[xix].

A deeply engrained culture of impunity exists in the Philippines with the government systematically failing in its responsibility to adequately investigate these crimes or prosecute and punish the perpetrators[xx]. The Philippine Commissioner on Human Rights has warned that the country is in danger of being blacklisted by the UN because the ‘authorities have failed to stop the spate of killings and abductions of activists’. In 2007 the UN Special Rapporteur on Extra-Judicial Summary or Arbitrary Killings, Mr Philip Alston visited the Philippines in response to growing concern about the number of extra-judicial in the country.

A climate of fear exists among legitimate protesters against government policies and commercial projects due to the lack of effective protection of the right to peaceful protest and opposition. This has been compounded by concerns around the recently enacted anti-terrorism legislation, the 2007 Human Security Act, which NGOs fear will be used to label and silence those questioning government policy, including its policy with regard to mining.

The Right to Liberty and Security of Person (Security firms and Militarization)

The global trend of increasing human rights violations associated with mining security and militarization is evident in the Philippines . Following his Philippine country visit in 2003, the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous Peoples, Professor Rodolfo Stavenhagen, stated that the ‘militarization of indigenous areas is a grave human rights problem’.

Members of the Subanon indigenous people, from Zamboanga del Norte Province, Mindanao Is-land, told the FFT that 169 armed security guards, hired by a Canadian mining company, TVI Pacific, were manning checkpoints and blocking access to their ancestral domain. Presentations to the FFT by church and other groups report that the use of intimidation and force by mining security forces, military and police against indigenous peoples and small-scale miners at mining sites is widespread.

In addition, militarization is associated with mining in conflict zones. Past payments of protection money by mining companies to armed groups has also been documented. The issue arose during a 2005 Canadian parliamentary hearing into the activities of Canadian mining companies overseas. In taking evidence the parliamentary committee referred to statements made by a former project manager of a mine located in Southern Mindanao where he claimed that it was the practice for the mine to make illegal payments of protection money to a range of terrorist and military groups[xxi].

Right to Access to Justice – Ineffectiveness, Influence on the Judiciary and Corruption.

Despite the existence of a relatively strong legal framework, lack of resources, corruption and ineffectiveness of the judiciary have greatly hindered the ability of indigenous and local communities to obtain timely and effective resolution of cases submitted at municipal and regional trial courts. The FFT heard from the Subanon at Mount Canatuan and Subaanen of Midsalip of cases rendered moot through court inaction and of petitions and demands that have not been addressed by the responsible administrative bodies, such as the NCIP and DENR.[xxii]

At the Philippine government’s mining road show in London in June 2005, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Jose de Venecia, told international mining investors about his role in the controversial reversal of a Supreme Court decision on the constitutionality of the Mining Act in the La Bugal-B’laan Tribal Ass’n v. Ramos case of 2004. He announced that, together with the Chamber of Mines ‘we mounted a strong campaign to get the Supreme Court to reverse itself. It was a difficult task to get 15 proud men and women of the Supreme Court to reverse themselves. But we succeeded. Finally, the law was declared constitutional.’ This statement appears to indicate that the Philippines judiciary may be vulnerable to pressure from legislators.

The Philippines was categorized by Transparency International in 2004 as suffering from ‘rampant corruption’. The mining sector in the Philippines appears to be no exception to this. The FFT heard allegations of corruption linked with mining at local government level. A 2005 European Commission report stated that the DENR had ‘shied away’ from introducing ‘internal controls to curb corruption, which has traditionally been notorious with respect to illegal logging and mining concessions’.

Right to Freedom of Religion and Belief – Protection of Sacred Sites

The lack of respect of indigenous peoples’ traditional religions and beliefs has resulted in the destruction of their sacred mountains and sources of their medicinal plants. In the case of the Subanon at Mount Canatuan this happened despite the recognition of their ancestral domains and their pleas to the responsible government bodies that these sacred places be safeguarded.

iv) Cooperation of the country under review with human rights mechanisms, and with NHRIs, NGOs, rights holders, human rights defenders, and other relevant national human rights …;

At the international level the Philippine Government’s track record with regard to adhering to its reporting obligations under international treaties has been poor. In its 2002 report the HRC raised the issue of the effectiveness of the implementation of IPRA and its protection of indigenous peoples in the context of mining operations on their lands. CERD also raised this issue at its last review in 1997 and more recently under its early warning and urgent action procedure in 2007. The Philip-pines has accepted visits of a number of UN Special Rapporteurs who have also addressed the issues raised in this submission in their reports.

v) Achievements made by the country under review, best practices which have emerged, and challenges and constraints faced by the country under review;

IPRA, which was enacted to facilitate compliance with the constitutional obligations and the rights of indigenous peoples, is regarded by many as a landmark piece of legislation. However, as noted, its implementation, particularly with regard to recent procedural revisions, has been found wanting and is seriously threatening the culture and survival of indigenous communities.

vi) Key national priorities as identified by NGOs, initiatives and commitments that the State concerned should under-take, in the view of NGOs, to overcome these challenges and..;

a) It is imperative that the weaknesses of the NCIP, which to date has proved incapable of implementing IPRA and upholding indigenous peoples’ rights, are urgently addressed. Its lack of legitimacy and credibility in the eyes of indigenous peoples requires that the commission be either completely reformed or replaced. To ensure representation of indigenous peoples, the staff and commissioners of the NCIP must be chosen by indigenous peoples themselves, and not the office of the President. The commission must also be granted sufficient financial and human resources with which to carry out its mandate and its operations of must be free from political interference.

b) To ensure implementation of laws to protect indigenous people in the Philippines , there must be independent monitoring of FPIC processes. Participation in such monitoring by civil society, the National Human Rights Commission, relevant religious and academic institutions and indigenous peoples organizations is necessary ensure credibility of the process and the provision of independent accurate information.

c) The FPIC implementing rules and regulations, which fail to adhere to the intent of IPRA, by imposing restrictions on the time, manner and process of FPIC that are not in conformity with the customs, laws and traditional practices of indigenous communities, should be revoked.

d) Measures to improve the regulation of mining in the Philippines should be urgently introduced. The DENR should be restructured to eliminate the conflict of interest in its mandate. The office for approval of exploration and mining applications should be divorced from the office of environ-mental regulation, monitoring and legal enforcement.

e) In keeping with the spirit of the Philippine Constitutional provisions and IPRA the Philippine Government should ratify ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples.

f) In line with the 1987 constitutional recognition of the prior rights of indigenous peoples to their ancestral lands the Government should end the contradictory practice of allowing mining companies to assert prior rights over indigenous peoples’ (the traditional owners/occupiers of the land) ancestral lands.

g) The Philippine Government should take urgent steps to halt the continuing spate of killings of politically active citizens and prosecute the perpetrators.

vii) Expectations in terms of capacity-building and technical assistance provided and /or recommended by

NGOs through bilateral, regional and international cooperation.

a) All Governments should be encouraged and assisted to establish binding frameworks to regulate mining, and ensure access to courts and other effective mechanisms of redress within home countries of transnational mining companies and financial institutions that support them.

b) The World Bank Group should uphold its mandate to help reduce world poverty and protect the environment by halting any promotion and support for mining expansion in the Philippines under current conditions. The Bank should assist with the country’s sustainable development by providing technical and financial support for the protection and development of renewable resources, sustain-able activities and poverty reduction programs and support Strategic Environmental Appraisals (SEAs) of the islands and regions targeted for, or affected by, mining. The Bank should be strictly guided by its OP 4.10 on Indigenous Peoples, OD 430 on Involuntary Resettlement and IFC Safe-guard policies, all of which should be updated to be in compliance with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, specifically reflecting the provisions of Article 32 of the Declaration requiring Free Prior Informed Consent as opposed to the Banks inadequate standard of Free Prior Informed Consultation. The Asian Development Bank should adopt and implement similar policies.

c) The WHO should consider conducting a study on the impact of cyanide and heavy metals on the right to health of Philippine indigenous and local communities impacted by mining.

d) UNESCO with the assistance of other relevant UN bodies and individuals (e.g. Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion and Belief) should address the issue of discrimination with regard to indigenous religions and beliefs and establish the mechanisms necessary for the formulation of 'comprehensive policies based on recognition of religious, political, social, cultural and spiritual rights, including of indigenous peoples sacred sites' as called for during the 6th session of UNPFII.

e) Where requested to do so by indigenous communities, the relevant UN Agencies could assist in the monitoring and provision of independent information in FPIC processes..

[i] The destruction of Mount Canatuan , the sacred mountain of the Subanon people in Zamboanga del Norte province, Mindanao , is a clear example of this. Similarly, the Subaanen of Midsalip in Zamboanga del Sur fear a similar fate for Mount Pinukis , also sacred mountain.. See Attached report Mining in the Philippines : Concerns and Conflicts pages 3 – 8 & Appendix 2. See also Mining a Sacred Mountain , Human Rights Impact Assessment, Rights and Democracy, 2007, available at http://www.humanrightsimpact.org/publications/item/pub/202/

[ii] In October 2002, a meeting was called by NCIP supposedly to obtain the consent of the Subanon of Mount Canatuan. The venue rather than being in the community was in a hotel in Zamboanga City . An employee of the mining operations of TVI proposed a motion to allow the mining operations. A vote was forced in contravention of IPRA’s requirements as well as Subanon traditional practices. 16 out of the 30 members voted in favour and the resolution allowing mining was adopted in the absence of a consensus being reached or the presence of any community observers. Strong objection was voiced by a number of those present as this process was a violation of customary law and IPRA. The Subanon court subsequently found that many who voted in favour of the resolution were not qualified under their customary law to act as representatives of the Subanon people. The NCIP has facilitated a similar decision making process in Midsalip where by leaders of questionable legitimacy were given the power to decide for the Subaanen people. The decision were taken in a manner which violates their customary laws which require consensus decisions be reached. See Submission to the Committee on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination regarding Discrimination against the Subanon of Mt Canatuan, Siocon, Zamboanga del Norte , Philippines in the context of large-scale gold mining on their ancestral domain. CERD 71st Session, 30th July – 17th August 2007 (henceforth Subaanon CERD Submission) para 27. Also Petition filed by Subaanen of Midsalip to NCIP 20 June 2006 Demand for Non Issuance of Certificate Pre-condition on file with FFT

[iii] These restrictive and discriminatory timeframes were introduced in the 2002 FPIC guidelines. A total of 55 days was allocated for all steps with fixed time windows on each step of the FPIC process - namely notice period, consultative community assemblies, community consensus building and decision making meetings. 15 days were allocated to community consensus building. The 2006 revision retails this restrictive timeframe requiring that all steps involving the indigenous peoples in the FPIC process be completed within 55 days but does not allocate fixed time windows to each step. This has the potential to reduce the community consensus building period to even less than 15 days.

[iv] Id. Indigenous communities at Mount Canatuan , Midsalip and Mindoro have all attested to and provided clear evidence of the NCIP’s involvement in the creation of ‘representative’ structures that do not adhere to their traditional law and practices. See also ‘National Consultation with the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous Peoples February 2, 2007’ available at http://ecozoic.multiply.com/journal/item/22

[v] Past experiences of communities throughout Mindanao and in Mindoro attest to such practices. For examples of these practices see attached report Mining in the Philippines : Concerns and Conflicts page 13 & also Appendix 5

[vi] For example, Mining Ombudsman case report: Didipio gold and copper mine, Oxfam Australia , September 2007 and cases documented by Indigenous Peoples organizations in the Philippines on file with FFT.

[vii] The Subaanon of Midsalip have provided the FFT with extensive documentation regarding problems of the recent FPIC processes conducted there which is illustrative of this pattern. They also provided petitions that had been forwarded to the NCIP and DENR. According to their documentation the only information provided at the FPIC process was by individuals with a direct interest in mining. Many of the promises made were unrealistic and the potential impacts were not addressed. The NCIP official, whose role is merely to facilitate instead spoke in favour of mining. At the same time community members wishing to raise their concerns were not allocated sufficient time to do so. Following these processes complaints were submitted to the Ombudsman and petitions to the NCIP highlighting this fact but no action was taken to address the issue.

[viii] As of 2003, there had been at least 16 serious tailings dam failures in the preceding 20 years and over 800 abandoned mine sites have not been cleaned up see Chronology of Tailings Dam Failures in the Philippines (1982-2002) Compiled by Philippine Indigenous Peoples Links http://www.piplinks.org last updated: 29 October 2003 see also Ronnie E Calumpita, ‘857 abandoned mines pose health menace, say NGOs’, The Manila Times Reporter, 11 October 2005.

[ix] UNEP report Final Report of the United Nations Expert Assessment Mission Marinduque Island, Philippines 30 September, 1996 pp65, 69, which declared the river biologically dead.

[x] Oxfam Australia Case Study: Marinduque Philippines Available at http://www.oxfam.org.au/campaigns/mining/ombudsman/ 2004/cases/marinduque/marinduque.html ‘Although the mine closed almost a decade ago, communities throughout Marinduque report that their daily lives and environment are still affected by the mine… Women and men of Marinduque told the Ombudsman that they have experienced loss of livelihoods and serious health impacts which they attribute to the mine. Fish are no longer abundant or healthy and some fishermen have lost limbs, they believe as the result of long-term exposure to arsenic in the mine waste. Children have also suffered lead poisoning which community members attribute to the mine. Several children have undergone painful blood detoxification and at least three have died.’

[xi] “President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo’s Administrative Order No. 145, created the Rapu-Rapu fact-finding commission. See Findings and Recommendations of the Fact-Finding Commission on the Mining Operations in Rapu-Rapu Island May 19th 2006 Executive Summary p12, p24. The DENR’s own report also stated ‘The main cause of the two incidents can largely be attributed to the negligence and un-preparedness of the company to address such emergencies.’ DENR Assessment of the Rapu-Rapu Polymetallic Project P35 available at http://www.greenpeace.org/raw/content/seasia/en/press/reports/denr-assessment-of-the-rapu-ra.pdf.

[xii] See BFAR tests: Rapu-Rapu waters safe for marine life - But Lafayette not yet cleared in fish kill By Ephraim Aguilar, Inquirer 9 November 2007 http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/breakingnews/regions/view_article.php?article_id=99885 see also Lafayette Mining - Rapu-Rapu Folk Going Hungry after Fish Kill, Lisa Ito, 11-17 November 2007 Bulatlat, Vol. VII, No. 40 - http://bulatlat.com/2007/11/rapu-rapu-folk-going-hungry-after-fish-kill-locals-reportpossible-seafood-poisoning

[xiii] In its mining plan the DENR states that ‘8.5 million hectares or 94.4 percent of mineralized areas [approximately 28 per cent of the total land area of the Philippines ] have yet to be developed’, without reference to potential environmental damage & impacts on livelihoods based on agriculture & fisheries.

[xiv] ‘What does it gain a nation to be short-sighted and merely think of money when an irreparable damage to the environment will cost human lives, health, and livelihood capacity of our farmers and fisherfolk endangering the food security of our people?’ Then DENR Secretary Heherson Alvares 2001.

[xv] International experience suggests that if pursued on the scale currently proposed by the Philippine government, mining

could weaken the food security and threaten the right to food of affected communities and even of the country as a whole. According to the Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people, Rodolfo Stavenhagen Mission to Philippines E/CN.4/2003/90/Add 3, para 63 threats to health were one of the negative impacts of mining in the Philippines that urgently needed to be halted.

[xvi] According to the NEDA development plan, ‘the management of watersheds has not been properly given attention. This has led to shortages of water for irrigation, industrial and domestic uses and is thus likely to negatively affect future development initiatives.’

[xvii] Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Mr. Jean Ziegler, submitted in accordance with Commission on Human Rights resolution 2000/10 UN Doc E/CN.4/2001/53 7 February 2001 para 14

[xviii] Investigations into the issues of extra-judicial killings in the Philippines have been conduced by, amongst others, Amnesty International, The UN Special Rapporteur on Extra-judicial Summary or Arbitrary Killings Mr Philip Alston and the Melo Commission, an independent commission created under the order of the President of the Philippines.

[xix] Karapatan estimate the number at 18 extra-judicial killings of mining activists see http://www.kalikasan.org/kalikasan-cms/?q=node/145. Other sources also identify extra-judicial killings of mining activists but do not provide estimates of the total numbers killed. While the number of and reason for extra-judicial killings can very be difficult to ascertain and verify there appears to be widespread agreement that mining activists are among the target groups. International human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch (HRW) identified anti-mining activists along with political activists, student activists, political journalists, clergy, and agricultural reformers as the groups targeted. Out of a sample of 13 cases that HRW investigated 2 were anti-mining activists: Pastor Isias de Leon Santa Rosa in Bicol and Manuel Balani both killed in 2006. In both cases the evidence available points military involvement in the killings see http://hrw.org/reports/2007/philippines0607/4.htm see also http://www.miningwatch.ca/index.php?/ Newsletter_22/Political_Killings_Increase

[xx] A 2006 Dutch Belgian delegation of lawyers and judges described a developing ‘culture of impunity’ Dutch Lawyers for Lawyers Foundation, From Facts to Action Report on the Attacks Against Filipino Lawyers and Judges. The International Fact Finding Mission (IFFM), 24 July 2006 pages 37–39.

[xxi] Statement by Allan Laird to the Subcommittee on Human Rights and International Development of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade Meeting May 18, 2005. Ottawa Kingking Mines Inc. Corporate Support of Terrorism in the Philippines available at http://www.dcmiphil.org/Allan_Laird%27s_Statement.pdf

[xxii] Subaanon CERD Submission para 64 – 68, lists a number of these cases filled by the Subanon of Mount Canatuan.

No comments:

Post a Comment