Tsk, tsk, so much for responsible mining. So much for sustainable development.

From http://praxispictures.blogspot.com/

Monday, May 12, 2008

Beneath the 7,107 islands that make up the Philippines, lies one of the world’s largest mineral resources. The Philippines is the second largest gold producer in the world (behind only South Africa), and the third largest copper producer. The countries’ mineral wealth is estimated to be somewhere between US$840billion and US$1trillion. But the record of large scale mining in the Philippines is nothing short of disastrous. The social and environmental impacts of these mines have clearly not been a priority to the Philippine government, or to the foreign investors who are profiting from these ventures. The extraction of these treasured metals comes at a high price. People who were already marginalized and living in poverty to begin with are losing what they most treasure – families are being torn apart, livelihoods destroyed, ecosystems ruined, and ancient indigenous cultures are being eroded.

Beneath the 7,107 islands that make up the Philippines, lies one of the world’s largest mineral resources. The Philippines is the second largest gold producer in the world (behind only South Africa), and the third largest copper producer. The countries’ mineral wealth is estimated to be somewhere between US$840billion and US$1trillion. But the record of large scale mining in the Philippines is nothing short of disastrous. The social and environmental impacts of these mines have clearly not been a priority to the Philippine government, or to the foreign investors who are profiting from these ventures. The extraction of these treasured metals comes at a high price. People who were already marginalized and living in poverty to begin with are losing what they most treasure – families are being torn apart, livelihoods destroyed, ecosystems ruined, and ancient indigenous cultures are being eroded.These pictures tell the stories of some of the people whose lives have been affected by the Canadian mining industry. Three different provinces are visited – Benguet, Marinduque, and Oriental Mindoro. In Benguet, Lepanto Consolidated has been operating a gold mine since 1995. Canadian company Ivanhoe Mines holds shares of Lepanto. Marinduque was the site of the worst industrial disaster in Philippine history, where Canadian company Placer Dome operated a copper mine for thirty years. In Oriental Mindoro, Canadian Crew Minerals, who have recently relocated to Norway and changed their name to Intex Resources, has been attempting to open up a nickel mine despite local opposition.

Canada, home to about sixty percent of the world’s mining corporations, leads the way in the global mining industry. But some critics have labeled the mining industry as Canada’s number one contribution to global injustice. As the industry continues to shape the world we all live in, it is the hardships endured by the men, women, and children like these that make our way of life possible.

Trixie looks down at the tailings dam for the Lepanto gold mine in the province of Benguet, where the toxic waste from the mining process are dumped at a rate ranging between 1,500 and 2,500 metric tons per day. This is the third dam built here after the previous two collapsed.

Trixie looks down at the tailings dam for the Lepanto gold mine in the province of Benguet, where the toxic waste from the mining process are dumped at a rate ranging between 1,500 and 2,500 metric tons per day. This is the third dam built here after the previous two collapsed. According to a fact-finding mission led by British MP Clare Short, as of 2003, there had been 16 serious tailings dam failures in the Philippines in the past twenty years. Additionally, over eight hundred mine sites have been abandoned and have never been cleaned up. Cleanup costs are estimated in the billions of dollars and the damages caused are irreversible.

This particular dam has been completely inadequate against the torrential downpour during the yearly rainy season and is especially vulnerable to earthquakes as Benguet is directly above a fault line. For years the chemicals have been leaking out into the nearby river systems.

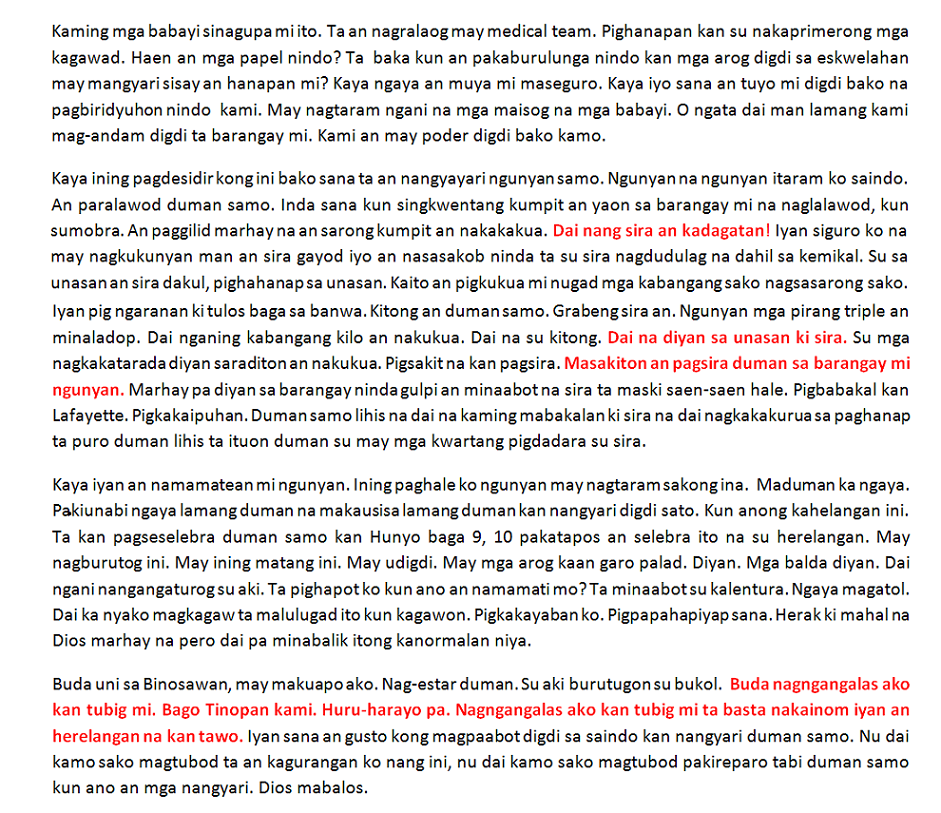

Just a few meters past the dam, contaminated water (left) - carrying with it cyanide, lead, copper, and mercury - joins together with the clean water (right) coming from the mountain springs into the river system.

Just a few meters past the dam, contaminated water (left) - carrying with it cyanide, lead, copper, and mercury - joins together with the clean water (right) coming from the mountain springs into the river system. Many mining sites in the Philippines are located in the mountains that act as watersheds for the surrounding river systems, which poses serious threats to those living downstream from the mines. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, contaminated water from mining operations poses one of the top three ecological security threats in the world.

The dangers surrounding mining are exacerbated in the Philippines by the additional risks from the high rainfalls, frequent typhoons and earthquakes, all of which increase the strain on the tailings dams making leaks almost inevitable.

In Cervantes, a few kilometers down river from Lepanto’s gold mine, Suley sits in the middle of her barren farm which has been contaminated by the toxic chemicals that have leaked out of the tailings dam and into the river system.

In Cervantes, a few kilometers down river from Lepanto’s gold mine, Suley sits in the middle of her barren farm which has been contaminated by the toxic chemicals that have leaked out of the tailings dam and into the river system. Her farm has been barren for ten years now. “If it wasn’t for the mine, we would be living a good life”, she says, “but now, life is very hard.” Before, Suley’s abundant farm more than adequately provided for her entire extended family. Now they are barely able to provide for their basic needs. Every year they try replanting fresh seeds hoping that the soil will eventually regenerate. They will do so again this year, but after ten years, nothing has changed.

According to the Save The Abra River Movement, the siltation and toxic pollution of the rivers deprives communities in Cervantes of about 7.33 million kg of rice worth US$2.27 million per annum.

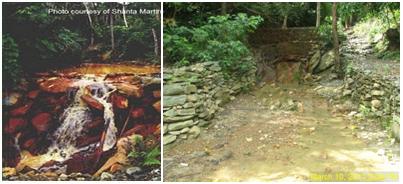

Remy washes her laundry in the poisoned Mogpog River in Marinduque. In 1993 one of the tailings dams of Placer Dome’s copper mine burst sending tons of mine waste raging down the river in a flash flood sweeping away homes, people and livestock. Three years later a second collapse sent waste in the opposite direction destroying the Boac river.

Remy washes her laundry in the poisoned Mogpog River in Marinduque. In 1993 one of the tailings dams of Placer Dome’s copper mine burst sending tons of mine waste raging down the river in a flash flood sweeping away homes, people and livestock. Three years later a second collapse sent waste in the opposite direction destroying the Boac river. After Fifteen years both rivers remain biologically dead and contain dangerous levels of toxic chemicals. Dead trees and other debris can still be seen all along the rivers. But people here have no other water sources to rely on. The company continues to deny any responsibility for what was the worst industrial disaster in Philippine history. After being ordered by the government to clean up their mess, the company responded by packing their bags and sneaking out of the country.

“Imagine...being forced into a situation where you lived in a house...and a contractor puts a huge swimming pool up on your roof. You then suddenly receive a secret report that says the roof can cave in at any time and the water can drown you and your children who live below!...How would you feel if you had no other place to live? If you feel desperate, you have just put yourselves in the shoes of...almost 100,000 villagers in my home province of Marinduque.” - Congressman Edmund Reyes from Marinduque.

“Imagine...being forced into a situation where you lived in a house...and a contractor puts a huge swimming pool up on your roof. You then suddenly receive a secret report that says the roof can cave in at any time and the water can drown you and your children who live below!...How would you feel if you had no other place to live? If you feel desperate, you have just put yourselves in the shoes of...almost 100,000 villagers in my home province of Marinduque.” - Congressman Edmund Reyes from Marinduque.The San Antonio Pit contains millions of tons of mine waste being held back by failing dams. According to a leaked document from Placer Dome’s own environmental consultants, “failure of the dam is a virtual certainty in the near term”. When the Philippine government ordered Placer Dome to make the necessary repairs, and clean up the mess from two previous dam failures or face criminal charges, Placer Dome responded by pulling out personnel from the Philippines without a word to anyone.

Eighty years old, Thomas used to bathe in the Mogpog river every day when he was younger. His body is now covered with skin discolouration which he started developing about forty years ago when Placer Dome’s mine was in full operation.

Eighty years old, Thomas used to bathe in the Mogpog river every day when he was younger. His body is now covered with skin discolouration which he started developing about forty years ago when Placer Dome’s mine was in full operation. Marinduque has never been able to afford conducting a full medical survey of the island, but smaller studies have shown that, of 59 children tested, every one of them had unacceptable levels of lead in their blood, and a quarter of them had dangerous levels of cyanide in their blood. Soil and air samples also showed unacceptable levels of dangerous chemicals.

When Placer Dome left Marinduque, they left behind them the mess from years of dumping mine waste into Calancan Bay; the island’s two main rivers of Mogpog and Boac were poisoned by separate dam collapses in 1993 and 1996; a population suffering from heavy metal contamination; stripped forests; and a nine-hole golf course. The province never saw a single centavo of the profits that Placer Dome raked in.

When the first dam collapsed in 1993, the flash flood of toxic waste swept away Thomas’ treasured cow and he nearly drowned. With the San Antonio Pit now on the verge of collapse, Thomas knows that his home will be one of the first ones swept under by the coming flash floods, but he has nowhere else go. With his already deteriorating health, he stands little chance of surviving.

Wilson was a fisherman living in Calancan Bay in Marinduque where Placer Dome used to dump its mine waste. Over a period of sixteen years, Placer Dome dumped 200million tons of mine waste into the shallow coral-rich bay despite vocal opposition from the community. The president of the company, John Dodge, continues to maintain that the fishermen of Calancan Bay “have not suffered in any way because of the tailings disposal.”

Wilson was a fisherman living in Calancan Bay in Marinduque where Placer Dome used to dump its mine waste. Over a period of sixteen years, Placer Dome dumped 200million tons of mine waste into the shallow coral-rich bay despite vocal opposition from the community. The president of the company, John Dodge, continues to maintain that the fishermen of Calancan Bay “have not suffered in any way because of the tailings disposal.” Before, most of the 15,000 villagers in the area made a living from fishing in the bay for a few hours every other day. Now, there are more fishermen than fish, and the men have to go far out to sea everyday. One day many years ago Wilson went out into the bay with a small cut in his leg. As a result, Wilson suffered from mercury poisoning rendering his legs useless. One leg has been amputated, the other one will have to come off as well.

“It’s just a picture, it won’t change anything. I can’t ask you to do this”

“It’s just a picture, it won’t change anything. I can’t ask you to do this”“I want to. Look, the dam could break at any time, maybe next week, maybe tomorrow, I don’t know. But I do know that when it does happen, my house and my family will probably be destroyed. And just like last time, the company will deny responsibility. I want that picture to exist, so that people can know what happened. For that, I would be willing to sacrifice myself.”

With that a brave Marinduqueño, D., snuck a photographer in the back of a truck into Placer Dome’s old copper mine, successfully evading the armed guards still protecting the property. Here D stands in front of the San Antonio Pit, containing the millions of tons of mine waste which will eventually come crashing down on his home. His desire to put himself in harms way for the sake of this documentation is a stronger testament to the anxiety Marinduqueños have to live with every day than any picture can offer.

In Pili, Mindoro, Henry (second left) and his family enjoy a meal consisting of rice, fish and vegetables. The province of Oriental Mindoro is ranked third as the province which produces the most food in the Philippines, and is known as the “food basket” of the southern Luzon region.

In Pili, Mindoro, Henry (second left) and his family enjoy a meal consisting of rice, fish and vegetables. The province of Oriental Mindoro is ranked third as the province which produces the most food in the Philippines, and is known as the “food basket” of the southern Luzon region. The food security of Mindoro is under threat, however, by Crew Minerals’ (now Intex Resources) proposed nickel mine. The proposed mine site is located within a critical watershed area that provides the irrigation for 70% of the province’s vital rice fields and fruit plantations.

Despite widespread opposition to the mine from all levels of the local population, the company maintains that the local population welcomes the project. Crew has lied to the people of Mindoro by claiming that the proposed method of submarine tailings disposal is environmentally safe and practiced in their home country Canada, when in fact this method is banned in Canada.

Ramon, of the Alangan tribe in the village of Kisluyan, in Mindoro. Kisluyan is one of 26 indigenous villages that face the threat of displacement if Crew Minerals (now Intex Resources) opens up a nickel mine on their ancestral land.

Ramon, of the Alangan tribe in the village of Kisluyan, in Mindoro. Kisluyan is one of 26 indigenous villages that face the threat of displacement if Crew Minerals (now Intex Resources) opens up a nickel mine on their ancestral land. Although many of the indigenous peoples in the neighbouring villages are opposed to the mine, it has proven difficult to organize the groups to show their unified opposition and stand up for their rights. Traditionally the Alangan have been averse to confrontation.

Crew has taken advantage by forming their own group to pose as representatives of the affected indigenous communities to sign documents consenting to the mining operations.

Luningning, of the Alangan tribe, with her granddaughter in the village of Kisluyan. The Alangan are one of 8 indigenous tribes in Mindoro, known collectively as the Mangyans. The Mangyans, who once occupied the whole island, are peaceful people who shy away from confrontation. As more and more settlers began moving to the island, the Mangyans were gradually pushed higher and higher into the mountains. Now, with the proposed opening of the mine threatening to push them off their land, they are left with nowhere to go.

Luningning, of the Alangan tribe, with her granddaughter in the village of Kisluyan. The Alangan are one of 8 indigenous tribes in Mindoro, known collectively as the Mangyans. The Mangyans, who once occupied the whole island, are peaceful people who shy away from confrontation. As more and more settlers began moving to the island, the Mangyans were gradually pushed higher and higher into the mountains. Now, with the proposed opening of the mine threatening to push them off their land, they are left with nowhere to go. Maximo is the oldest member of Kisluyan and the acknowledged leader of the community. Maximo’s biggest worry is for the future generations. Living in relative isolation high in the mountains, the Mangyans have done well to hold on to their culture despite increasing external interference. The Mangyan have managed to ensure that their own traditional ways are taught in their schools, with Mangyan teachers, alongside the standardized Philippine curriculum.

Maximo is the oldest member of Kisluyan and the acknowledged leader of the community. Maximo’s biggest worry is for the future generations. Living in relative isolation high in the mountains, the Mangyans have done well to hold on to their culture despite increasing external interference. The Mangyan have managed to ensure that their own traditional ways are taught in their schools, with Mangyan teachers, alongside the standardized Philippine curriculum.For the Mangyan, their land is the very foundation of their identity. Generation after generation, the Mangyans have been taught to care for their land; “we take care of the land, and the land will take care of us.” Deeply superstitious, many of them worry that disaster will befall them if their lands – especially their ancestral burial grounds – are desecrated.

Stoking the flames, Jeff is a community activist working for ALAMIN (Alliance against the mine), a broad coalition of Mindoreños united in their opposition to the nickel project. ALAMIN has organized numerous peaceful demonstrations to show their opposition. However, members and supporters of ALAMIN have been subject to intimidation and have even been accused of being dissident-terrorists.

Stoking the flames, Jeff is a community activist working for ALAMIN (Alliance against the mine), a broad coalition of Mindoreños united in their opposition to the nickel project. ALAMIN has organized numerous peaceful demonstrations to show their opposition. However, members and supporters of ALAMIN have been subject to intimidation and have even been accused of being dissident-terrorists. The Philippines is one of the hot spots of the so-called global “War on Terror,” so such accusations are not to be taken lightly. As documented by Amnesty International and the United Nations, human rights abuses have been reported all across the Philippines against legitimate political and environmental activists. Since the current administration of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo took office in 2001, there have been over 700 reported extra judicial killings of such activists.

Albert has worked in the Lepanto mine for fifteen years trying to support his family of ten. But his wages are not enough to support all of them so his wife has had to leave for the city with their four oldest children to sell fruit in the market.

Albert has worked in the Lepanto mine for fifteen years trying to support his family of ten. But his wages are not enough to support all of them so his wife has had to leave for the city with their four oldest children to sell fruit in the market. Many of the men risking their lives underground say they feel exploited as they struggle to provide for their families while the company profits in the millions. The miners have no masks to protect them from chemicals and dust, they work wearing nothing but helmets, boots, and briefs, and have to pay for their own treatment when they fall ill.

Albert has no doubt that it’s a sacrifice he’s willing to make. “My family”, he says, “are my inspiration.” Together with his wife, they are putting their children through school in the hope that they will have better lives. It is this hope that gets him out of bed every morning to go back underground.

Lilia’s husband, Peter, had worked at the Lepanto mine for seventeen years when all 1,787 workers went on strike in 2005. The workers were on strike for three months demanding better wages, benefits and job security to reflect the dangers of their jobs. Management refused to meet their demands and responded by firing the 19 union leaders behind the strike, including Peter. After lengthy negotiations, the 19 union leaders eventually accepted their dismissals in exchange for the reinstatement of the other striking workers. The labour disputes have been ongoing with workers complaining that the company often delays or withholds their salaries to control them.

Lilia’s husband, Peter, had worked at the Lepanto mine for seventeen years when all 1,787 workers went on strike in 2005. The workers were on strike for three months demanding better wages, benefits and job security to reflect the dangers of their jobs. Management refused to meet their demands and responded by firing the 19 union leaders behind the strike, including Peter. After lengthy negotiations, the 19 union leaders eventually accepted their dismissals in exchange for the reinstatement of the other striking workers. The labour disputes have been ongoing with workers complaining that the company often delays or withholds their salaries to control them.Peter has been trying to find a new job without any luck for two years and recurring health problems have been making his job hunt increasingly difficult. With Peter unable to find work, the burden of supporting the family now falls on the shoulders of his wife Lilia, sitting here with their daughter Trixie. Lilia has no formal education so her prospects are limited. The only real option available to her is to work abroad as one of the millions of Filipino domestic servants employed all over the world. “I would like very much to work in Canada”, she says, “it must be like paradise there...do you know anyone who needs a house worker?”

But even in places like Canada, she knows Filipino domestic workers are alone and vulnerable. About a month before this picture was taken, she heard reports about a girl from the neighboring town of Ifugao who was murdered while working as a domestic servant in a mansion in Toronto. But apart from her personal safety, what troubles Lilia most is the thought of being separated from her family.

As the sun sets over the mountains of Benguet province, Lilia and Trixie walk along Lepanto’s airport runway near their home where all the gold is flown out of the province. The pattern has been repeated many times across the Philippines; the companies come in promising to bring with them jobs, development and prosperity. In reality, the experiences of the people of the Philippines show that large-scale corporate mining destroys, pollutes, and disrupts agricultural economies, and displaces indigenous peoples. While the mines do generate a great deal of wealth, local communities rarely see any of it.

As the sun sets over the mountains of Benguet province, Lilia and Trixie walk along Lepanto’s airport runway near their home where all the gold is flown out of the province. The pattern has been repeated many times across the Philippines; the companies come in promising to bring with them jobs, development and prosperity. In reality, the experiences of the people of the Philippines show that large-scale corporate mining destroys, pollutes, and disrupts agricultural economies, and displaces indigenous peoples. While the mines do generate a great deal of wealth, local communities rarely see any of it. The global demand for these metals have been skyrocketing, and the mining industry is booming. Yet, in places like the Philippines where these metals are found, the effects will be felt for generations. Families are being torn apart, indigenous cultures are being eroded, livelihoods lost, and ecosystems destroyed – all for someone else’s treasure.

No comments:

Post a Comment