Down the mine: Lafayette's lesson

Andrew Hewett

December 29, 2007

http://business.theage.com.au/down-the-mine-lafayettes-lesson/20071228-1jcl.html

AUSTRALIAN mining company Lafayette, operator of the Rapu Rapu mine on the small island of the same name in the Philippines, has just gone into voluntary administration. The news may raise eyebrows given the mining boom, but not everyone is surprised.

The story of Lafayette's mining operation and its financial failure resonates with a lesson that Oxfam Australia has long observed: a company that fails to obtain and retain a social licence to operate, in other words one that operates without community approval, is not viable.

Other Australian mining companies in the Philippines and elsewhere should heed Lafayette's rise and fall and take note of this cautionary tale.

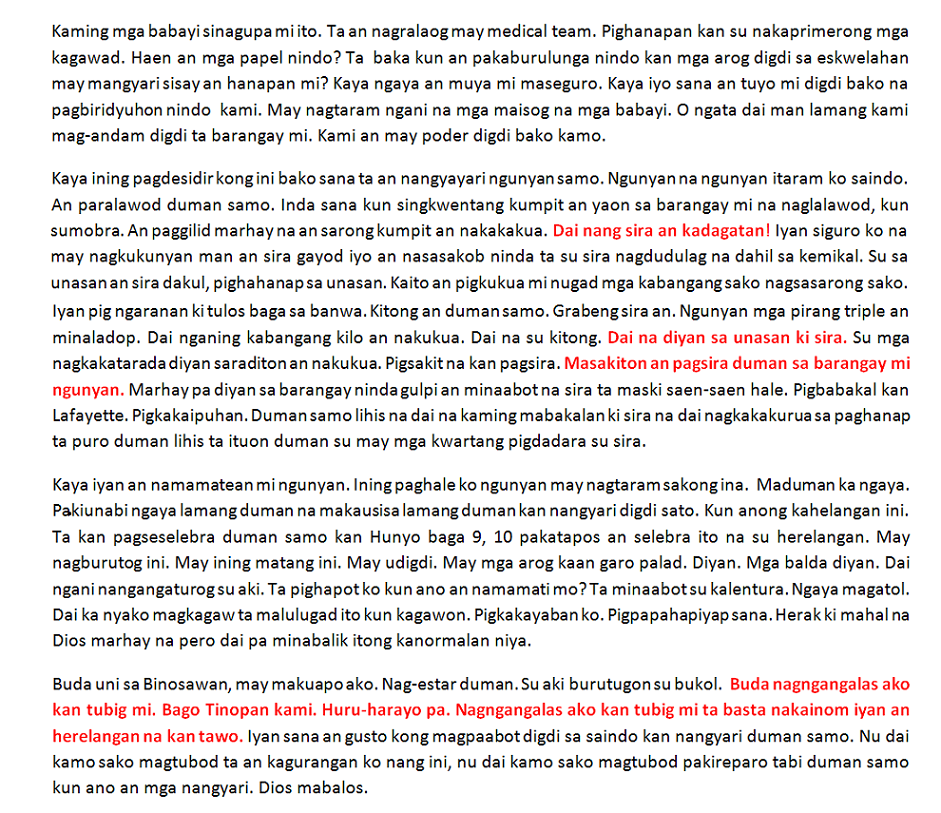

Initially lauded as the darling of the Philippines' mining revival program, Lafayette quickly turned sour for local fisherfolk. Just months after the start of mine operations in 2005, two cyanide-laden spills into the sea killed fish and created consumer fear. People refused to buy fish from the island. Communities on the island and surrounding the bay, whose livelihoods depend on selling fish, struggled to feed their families. A government-established fact-finding commission accused the company of gross negligence for failing to establish environmental safeguards.

Following the request of community members, Oxfam Australia's mining ombudsman has been investigating community complaints about the Rapu Rapu mine. The result of our investigations, which included interviewing more than 130 stakeholders in the Philippines, is impossible to ignore. Among those interviewed were fisherfolk, whose livelihoods have been affected by fish kills associated with the mine's operation, local councillors, who are tired of waiting on empty promises for the social development projects Lafayette said would come, and the provincial governor, who complains bitterly that the mine pays no taxes that would benefit the region. Few people who are not paid directly by the company expressed any desire to see the mine continue.

Meanwhile, ANZ and other "Equator Principle" banks, which have signed on to a set of social and environmental benchmarks that should govern their lending decisions, continued to prop up the company.

After another fish kill in recent months that affected a community that had experienced the earlier fish kills, more than 150 protesters stormed the provincial government building last week and demanded the closure of the mine. Before Lafayette, they said, there were no fish kills.

Despite national regulatory agency attempts to convince locals that the latest fish kill was not associated with the company, they said enough was enough. So too, it would appear, have the banks, which are now owed about $250 million by Lafayette.

The real question now will be what happens to those communities on Rapu Rapu in the wake of the financial failure of Lafayette. Will the mine be abandoned, as so many other mines have been in the Philippines, leaving the local communities to deal with the legacy of continued pollution of their waters and fisheries? Will the administrators start a fire sale of the mine to try to pay off the company's debts to ANZ and others, which may result in another speculative operator without a commitment to social or environmental responsibility?

Or will ANZ and the other banks that have signed the Equator Principles use this opportunity to demonstrate their commitment to social and environmental responsibility?

To date, the company has not been required by Philippine regulators to set aside money for the final rehabilitation of the mine. ANZ and the banks that supported Lafayette should show the communities of Rapu Rapu, who will live with the consequences of the failed investment, what "corporate social responsibility" means in practice. They can demonstrate this by ensuring that sufficient funds are set aside for the environmental rehabilitation of the mine and a sustainable development program for the communities of Rapu Rapu.

There is much to be gleaned from the Lafayette experience. The fundamental lesson for Australian mining companies operating in developing countries, as well as their financiers, is that mining projects that do not have and retain community approval ought not be pursued or financed.

For the Australian mining industry and government, the case demonstrates that an official complaints mechanism should be established in Australia to inquire into community dissatisfaction abroad. Doing so would ensure that Australian mining companies act in accordance with internationally accepted human rights and environmental standards. Compliance with these standards could have benefited all those who have missed out in the Lafayette case - communities, shareholders, mine workers and governments.

Andrew Hewett is executive director of Oxfam Australia.

1 comment:

i would like to join ur group in preserving mother earth..u can contact me on my e-mail: badz_butz2003@yahoo.com i love to see the mother earth especially when it is in its natural habitat

Post a Comment